The aim of this article is to present the main features of the Grande édition Marx et Engels (GEME)[1] project from a specific angle: that of the dissemination, in France and more generally in the French-speaking world, of the philological advances made possible by the second Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA-2).[2] The aim here is not to revisit the general theoretical issues[3] of the GEME project, but, rather, to situate it within the history of Marx and Engels editions in France in order to show the contribution made by the various volumes published since its launch in 2008 and to indicate how future volumes are likely to extend it.

From this perspective, in order to understand how the work of MEGA-2 is disseminated in France, three important points should be kept in mind. Firstly, although the GEME systematically draws on MEGA-2 for the establishment of texts and critical apparatus, it cannot be considered a simple French version of MEGA-2, as it does not replicate its structure, nor its ambition for exhaustiveness. The editors of the GEME are therefore always required to make choices from within the vast corpus of MEGA-2 volumes in order to determine which publications should be given priority. Secondly, the GEME is obliged to take into account the complex history of Marx and Engels editions in France during the 20th century, which constitutes an unavoidable backdrop for it. The editorial choices made by the GEME editors are therefore also partly dependent on this context, which, in a way, constitutes a horizon of expectations specific to the French reader. Thirdly, despite its recent nature, the GEME itself has a history, and the two decades that separate us from the publication of its first volume bear witness to a number of developments beyond the overall coherence of the project. These changes mainly reflect a desire to further improve the rigour of editorial work, both in terms of the procedures to be followed – with an increased role given to the GEME association, which supports the project, particularly through the organisation of regular research seminars – and in terms of the structure of the volumes, certain features of which, in particular the structure of the introductions and the content of the critical apparatus, have been systematised.

In this article, I will develop my argument in three stages. First, I will review the history of the dissemination of MEGA-2 in France prior to 2008 in order to explain how the GEME project came about. Secondly, I will attempt to show how the volumes of the GEME published to date have highlighted the research work carried out by the editors of MEGA-2. Thirdly, I will discuss the GEME’s future projects in order to indicate how the advances made by MEGA-2 can be disseminated to the French-speaking public in the years to come.

1/ From MEGA-2 to the GEME

More than thirty years separate the publication of the first volume of MEGA-2 in 1975 from that of the first volume of the GEME in 2008. However, this interval does not mean that MEGA-2 was not diffused in France during this period. Nor can these three decades be reduced to a simple period of preparation for what would become the GEME at the beginning of the 21st century. On the contrary, it was a period of tentative steps corresponding to the first phase of the reception of MEGA-2 in France, which was largely part of pre-existing publishing ventures. Indeed, the first French translations based on the work of MEGA-2 date from the late 1970s and early 1980s and complement the two major projects to publish the works of Marx and Engels that dominated the French landscape at that time: the one led by Maximilien Rubel at Gallimard in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade[4] and the one implemented within the Éditions sociales, linked to the French Communist Party (PCF). The two projects were based on principles that were in many ways antagonistic, both politically and philologically. While Rubel sought to present Marx as an anarchist, freed from the dogmatic distortion that, according to him, was already at work in Engels himself, Éditions sociales, on the contrary, placed Marx’s texts within the classical history of Marxism and rejected any artificial distancing of Engels’ contribution.

These conflicting principles also dictate significantly different approaches to the work carried out by MEGA-2. On Rubel’s side, recognition of the contribution made by MEGA-2 is inseparable from a constant mistrust, not only of the institutions that initiated it — the Institutes for Marxism-Leninism of the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic — but also towards the content of the volumes themselves, both in terms of the introductions and critical apparatus and the establishment of the texts. The launch of MEGA-2, which came after the first two volumes of the Gallimard edition had already been published, was thus described, in a foreword accompanying the third volume published in 1982, as “an important event [which] has renewed the basic data of any edition of Marx”, but this concession was immediately accompanied by sharp criticism of the “methods employed by those responsible for this edition, which consist of systematically drawing parallels between the faithfully edited teachings and the realities proclaimed as ‘communist’ or even ‘Marxist’”.[5] Returning to the issue in the foreword to the fourth and final volume published in 1994, Rubel reiterated more or less the same judgement, stating that “while it is undeniable that the specialist contributors sought an optimal solution to the editorial difficulties, thereby broadening our knowledge of the historical context of the genesis of Marx and Engels’ works, the fact remains that the project was flawed by its very political function in the ‘global offensive of Marxism-Leninism’’.[6] This is not the place to discuss the relevance of Rubel’s criticisms of the work carried out by MEGA-2, but it is clear that their significance is considerably weakened by the fact that his own editorial choices often had little to do with the philological rigour of a critical edition, as his detractors pointed out very early on.[7] The point to be made here is that Rubel’s reservations have led him to use MEGA-2 not as a reference edition in the original language but as just one source among many.

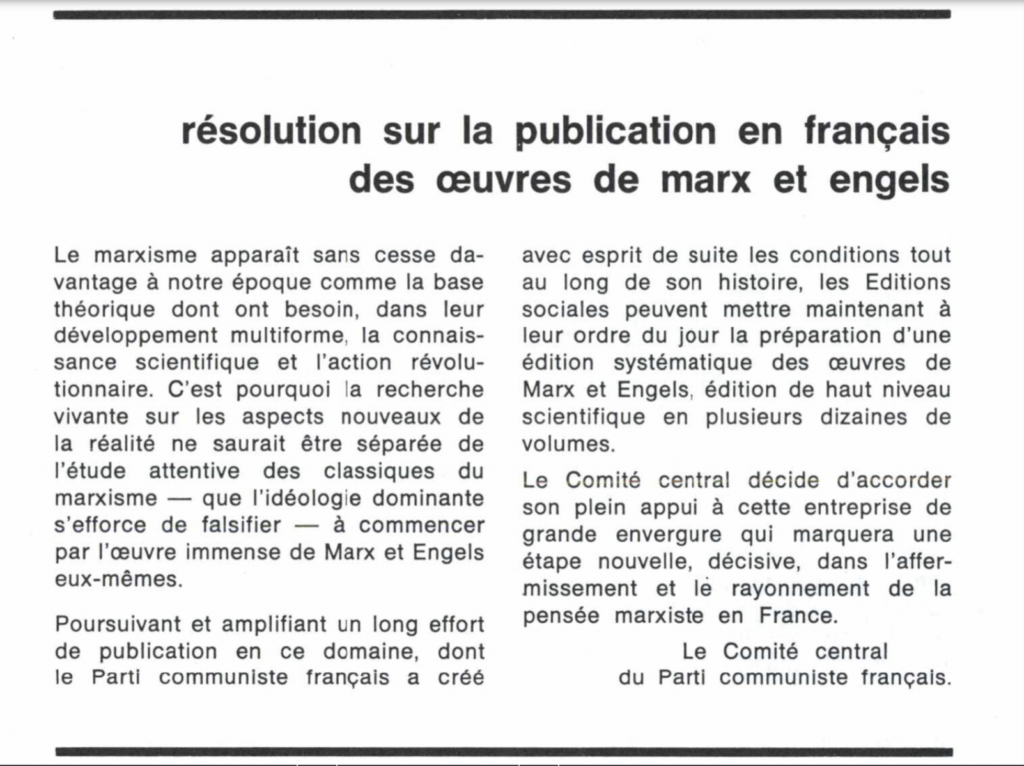

The situation was very different at Éditions sociales. Led since 1970 by Lucien Sève,[8] the PCF’s publishing house took a much more positive view of the MEGA-2 publications from the outset, considering them to be a valuable basis for its own work of publishing the works of Marx and Engels. Éditions sociales thus seized the opportunity offered by the first volumes of Section II very early on to make available to the French-speaking public certain important manuscripts coming within the critique of political economy, namely Notebooks I to V of the Manuscripts of 1861-1863[9] and the Manuscripts of 1857-1858 (Grundrisse),[10] published in 1979 and 1980 respectively, under the supervision of translator Jean-Pierre Lefebvre. Despite the pioneering nature of these publications, Lucien Sève did not really have the means to produce “a systematic edition of the works of Marx and Engels, a high-quality scientific edition in several dozen volumes”[11] as envisaged in the resolution passed on 26 October 1973 by the Central Committee of the PCF. The works published in this context nevertheless constitute decisive milestones in the process that would lead Lucien Sève himself to launch the GEME project in the early 2000s. In this new context, marked by the restructuring of MEGA-2 itself after the Fall of the Berlin Wall,[12] MEGA-2 increasingly appeared to be the natural basis for any serious French translation of the works of Marx and Engels, making it possible – without any direct link to the GEME project – the production of the most rigorous edition to date in French of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844,[13] published by Franck Fischbach at Vrin in 2007. It is therefore not surprising that the GEME immediately considered MEGA-2 to be “the decisive support that had been lacking until then for a French edition that could finally claim to be scientific”[14] and that it took care to conclude a cooperation agreement with the Internationale Marx-Engels Stiftung (IMES).

2/ The GEME, from 2008 to today

However, the conclusion of this cooperation agreement was not intended to make the GEME a French version of MEGA-2. The project’s initiators made it clear from the outset: what the GEME intends to retain from MEGA-2 is its “level of scientific rigour”[15] rather than its ambition for exhaustiveness. This level of scientific rigour refers primarily to fidelity to the text proposed by MEGA-2, which is evident in particular – since the second volume[16] was published in 2010 – in the integration of the pagination of MEGA-2 into the French text itself. As for the difference between the two editions, it can be measured primarily by the texts that the GEME intends to leave out: successive editions of the works for section I, some of the letters addressed to Marx and Engels for section III, and certain notebooks for section IV. But the difference between the two projects also lies in the fact that, unlike MEGA-2, the GEME does not have an overall provisional structure that would translate into a volume numbering system. The works published in the GEME are therefore the result of a preliminary selection made from the corpus of texts – itself still evolving – provided by the volumes of MEGA-2. This selection is always made on the basis of criteria of relevance linked to the previous history of French editions, the primary aim being to fill any gaps that may exist.

Looking at the eleven volumes published between 2008 and 2024, we can distinguish two main categories of texts, which explain the selection made by the GEME team. First, there is a collection of unpublished texts or texts that had previously been little disseminated and often unsatisfactorily translated into French. This is the case with Chapter VI of Book I of Capital, contained in the Manuscripts of 1863-1867, of which only the edition[17] produced by Roger Dangeville in 1971 at UGE existed, with a number of translation flaws. This is also the case for the collections of shorter texts that make up the two volumes[18] of Engels’ Early Writings, covering the periods 1839-1842 and 1842-1844 respectively, and the first volume[19] (1851-1852) of articles published in the New York Daily Tribune. In this case, the aim is both to reveal lesser-known aspects of the work of Marx and Engels and to place them precisely in the context of their development through chronologically organised collections.

On the other hand, the GEME’s ambition has been to draw on the contributions of MEGA-2 to produce rigorous editions of the most canonical texts by Marx and Engels. In this case, the scientific added value of these new editions lies both in the translation work, which aims to be more attentive to the systematic nature of the concepts used in the original language, and in the critical apparatus that accompanies the text itself. Two examples illustrate this particularly clearly. The first is the Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,[20] published in the GEME in 2018. This edition of the Kreuznach Notebooks of 1843 makes it possible to disseminate to the French-speaking public the work carried out in volume I/2 of MEGA-2 concerning the context in which the text was written, and to offer a translation of the text that accurately reflects Marx’s philosophical work based on Hegel’s writings. The second example is Volume II of Capital,[21] published in 2024. Beyond the undertaking of retranslating the work, this edition, which is based on the text published in 1885 as found in volume II/13 of MEGA-2, makes it possible to identify the changes made by Engels through a comparison with Marx’s manuscripts published in volume II/11.

3/ The future of the GEME

The continuation of the GEME’s publication work requires, as with the volumes already published, consideration of the projects to be prioritised in the coming years. While maintaining its ambition to cover the corpus of Marx and Engels’ works as broadly as possible, the GEME is primarily concerned, in the short term, with identifying a number of projects that its editorial teams are capable of completing. Unlike MEGA-2, the GEME does not have full-time staff working for a research organisation comparable to the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Its work therefore relies on the contributions of researchers who have other professional obligations related to their main activity.

In this context, two main directions can be mentioned here, corresponding to projects that are already underway or about to be launched. The first concerns the publication of works that are the logical continuation of volumes of the GEME published in previous years. This is primarily the case for the articles from the New York Daily Tribune, the French edition of which is set to continue, notably on the basis of volumes I/12 and I/13 of MEGA-2, corresponding respectively to the years 1853 and 1854, in order to make accessible a new set of texts, most of which are unpublished in French. This is also the case for Volume III of Capital, which, like Volume II published in 2024, should make it possible to compare the text published by Engels in 1894 in volume II/15 with Marx’s manuscripts contained in volume II/14.

The second major focus concerns Engels’ work more specifically and is the result of a reflection carried out in 2020 on the bicentenary of his birth. In this case, the emphasis was placed on the last two decades of his life, and, in particular, on the texts written after Marx’s death. Here again, the objective is twofold. On the one hand, it is to make accessible a large corpus of texts that are little known or even unpublished in English, which is the main objective of the collection of Political Texts (1883-1895) based on volumes I/30, I/31 and I/32 of MEGA-2, scheduled for publication at the end of 2025. On the other hand, continuing the work already carried out for the GEME edition of Socialism: Utopian and Scientific[22] in 2021, the aim is to produce genuine critical editions of the most famous texts from the latter part of Engels’ life. Work has already begun on Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy and The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. It could continue in the following years with Anti-Dühring and Dialectics of Nature, whose publication in the GEME could benefit not only from the contributions of volumes I/26 and I/27 of MEGA-2 – in particular, the chronological ordering of the manuscripts concerning Dialectics of Nature – but also from recent research on these texts[23].

Conclusion

Although the GEME is not intended to be a French version of MEGA-2, it can nevertheless be considered a gateway to it for the French-speaking public. MEGA-2 is an indispensable working basis for the GEME, guaranteeing, through its historical and critical rigour, the scientific nature of the project it intends to carry out. The GEME therefore makes it possible, on the one hand, to make certain fundamental contributions of MEGA-2 accessible in French and, on the other hand, to refer researchers wishing to undertake more specialised investigations to the latter. While the absence of an overall structure comparable to the numbering of the MEGA-2 volumes may appear to be a shortcoming in the overall architecture of the GEME project, it nevertheless allows for a certain flexibility in its implementation, which has some advantages in the case of a publishing venture that does not have large-scale institutional support.

This flexibility also allows the GEME to be a constantly evolving project, whose forms are not set in stone but can be reconfigured over time. To conclude, I will mention two cases that illustrate this point. The first concerns the digital component of the project. Although it was part of the project from the outset, it was slow to be implemented, mainly due to a lack of resources. However, it has recently been relaunched as part of a specific project to translate the 1844 Notes on James Mill, taken from volume IV/2 of MEGA-2, which is scheduled for publication in the GEME at the end of 2025. In this case, it was the complex intertwining of the different layers of text that led to the decision to forego a paper edition and lay the foundations for an electronic version that could serve as a model for the publication of other texts.

The second case refers to the issue of the constant progress of research conducted by the MEGA-2 team, which means that the volumes it publishes may, in some cases, become obsolete. This is the case with the pre-publication of the first two chapters of The German Ideology in the Marx-Engels-Jahrbuch 2003, which served as the basis for the GEME edition[24] published in 2014. Since then, volume I/5 of MEGA-2 in 2017 has offered not only a new edition of the text, but also, in the form of a separate volume,[25] a chronological arrangement of the manuscripts of the first chapter. In this context, the 2014 GEME edition itself will have to be revised in the coming years, the contours of which have yet to be outlined.

[1] The GEME is published by Éditions sociales and supported by the Fondation Gabriel-Péri. For more information, see https://geme.hypotheses.org/

[2] For more information, see https://mega.bbaw.de/de

[3] See Victor Béguin, “La GEME: projet théorique et enjeux de traduction”, La Pensée, N° 394, 2018, p. 17-28.

[4] See Aude Le Moullec-Rieu, “Marx’s Works in the ‘Bibliothèque de la Pléiade’: A Paradoxical Legitimation”, in Jean-Numa Ducange, Antony Burlaud (ed.), Marx, A French Passion. The Reception of Marx and Marxisms in France’s Political-Intellectual Life, Leiden, Brill, 2023, p. 127-136.

[5] Maximilien Rubel, “Avertissement”, in Karl Marx, Œuvres, Vol. III, Paris, Gallimard, 1982, p. xiii.

[6] Maximilien Rubel, “Avertissement”, in Karl Marx, Œuvres, Vol. IV, Paris, Gallimard, 1994, p. xvii.

[7] See Gilbert Badia, “Brèves remarques sur l’édition des œuvres de Marx dans la Bibliothèque de la Pléiade”, La Pensée, N° 146, 1969, p. 82-89.

[8] See Jean Quétier, “Das Marx’sche Werk ‘in Sicherheit’ zu bringen. Lucien Sève und das Projekt einer kritischen Marx-Engels-Werkausgabe in französischer Sprache”, Marx-Engels-Jahrbuch 2019/20, Berlin, p. 214-227.

[9] Karl Marx, Manuscrits de 1861-1863 (Cahiers I à V), Paris, Éditions sociales, 1979.

[10] Karl Marx, Manuscrits de 1857-1858 (“Grundrisse”), 2 Vol., Paris, Éditions sociales, 1980.

[11] “Résolution sur la publication en français des œuvres de Marx et Engels”, Cahiers du communisme, N° 12, 1973, p. 114.

[12] See Jürgen Rojahn, “Und sie bewegt sich doch! Die Fortsetzung der Arbeit an der MEGA unter dem Schirm der IMES”, MEGA-Studien, N° 1, 1994, p. 5-31.

[13] Karl Marx, Manuscrits économico-philosophiques de 1844, Paris, Vrin, 2007.

[14] “Ce qu’est la GEME”, in Karl Marx, Critique du programme de Gotha, Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2008, unpaginated.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Karl Marx, Le Chapitre VI. Manuscrits de 1863-1867, Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2010.

[17] Karl Marx, Un chapitre inédit du Capital, Paris, UGE, 1971.

[18] Friedrich Engels, Écrits de jeunesse, 2 Vol., Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2015-2018.

[19] Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, Les articles du New-York Daily Tribune, Vol. 1, Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2022.

[20] Karl Marx, Contribution à la critique de la philosophie du droit de Hegel, Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2018.

[21] Karl Marx, Le Capital, Vol. II, Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2024.

[22] Friedrich Engels, Socialisme utopique et socialisme scientifique, Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2021.

[23] See notably Rolf Hecker, Ingo Stützle (ed.), Engels’ “Anti-Dühring”. Kontext, Interpretationen, Wirkung, Berlin, Dietz Verlag, 2020 and Kaan Kangal, Friedrich Engels and the Dialectics of Nature, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

[24] Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Joseph Weydemeyer, L’Idéologie allemande, Chap. 1 and 2, Paris, Éditions sociales, GEME, 2014.

[25] See Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Deutsche Ideologie. Zur Kritik der Philosophie. Manuskripte in chronologischer Anordnung, Berlin, De Gruyter, 2018.