In an interview given in 2011, Peter Watkins remarked ‘I don’t think I’ve made a particularly radical film in forty years, not really’,[1] a remark that might surprise those who regarded him as one of the most important left-wing film directors of the second-half of the twentieth century. Watkins’ caution seems here to point to his difficulty in working against the television and cinema apparatus in which his films were situated, and of generating the political effects on the audience that he desired. Still, even if Watkins found himself dissatisfied with his results, his attempts undoubtedly produced a compelling and highly unusual series of films.

Born in Norbiton, Surrey, in 1935, Watkins was interested in becoming an actor after leaving school. But discovering 8mm film after his military service he turned instead to making short films, which led to his first feature film Culloden in 1964, made for the BBC, which narrates the 1746 Scottish battle in which the Jacobite army led by Charles Edward Stuart was defeated by British government forces. Already in Culloden, Watkins’ principal subjects are laid out: media, war and class. The film carefully describes, on the one side, the circumstances that led government soldiers into the army, their rations, their opinions on the war. On the other, it lays out the class system of the clans, where the clansmen function as ‘human rent’ for the chief. The film’s unusual form – presented in the style of a television news report – serves to situate the battle in a larger historical context and, somewhat paradoxically, given the association of this type of technique with notions of ‘distanciation’, creates a striking sense of immediacy. (More than thirty years later, in a documentary filmed on the set of his last film La Commune (Paris, 1871) from 2000, Watkins can be heard telling the actors not to avoid looking into the camera, because not looking into the camera ‘creates distance’).

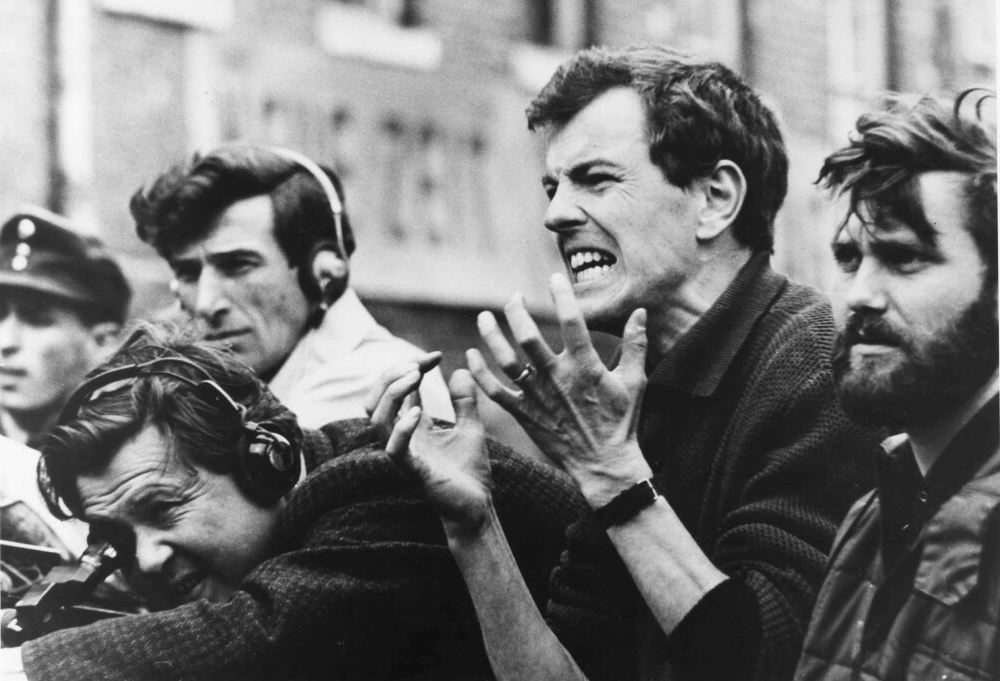

After Culloden, Watkins made The War Game in 1966, also for the BBC. This would become probably his best-known film, at least beyond cinephile circles, due to its visceral depiction of a nuclear attack on Britain (which used a similar pseudo-news report format) and, perhaps more importantly, due to the BBC refusing to show the film. Though the BBC claimed that the film was not being shown because it was too shocking, it has since become clear that the decision was made in collaboration with the Labour government, and was political in nature, due to the film’s presentation of the country’s civil defence plans as inadequate, something Labour particularly wanted to avoid at a time when they were about to recommend cutting civil defence spending.[2] The film would instead be released in cinemas. After the lukewarm response to his next film, Privilege, a fictional tale focusing on the relation between popular culture, the spectacle and social control, in 1967, Watkins left the UK and made the rest of his work elsewhere – in Sweden, the USA, Denmark and France.

Watkins’ early films up to 1971’s Punishment Park present power as highly centralised. For example, in The Gladiators (1969), the capitalist and communist powers organise the military spectacle of the ‘peace games’ together to secure the continuity of their own regimes, while Culloden underlines the fact that Charles Edward Stuart and his enemy counterpart the Duke of Cumberland are actually cousins, part of the same tiny European ruling elite. In these films, the media is seen as closely tied to the state and its disciplinary forms of governance, a fact borne out in reality by the collusion between the BBC and the British government in response to The War Game. The media here works through the withholding of information and deliberate manipulation by a centralised apparatus (in The Gladiators, the broadcast of the ‘peace games’ is modified at the flick of a switch by two individuals in a control room at the behest of generals).

These early films also already manifest the vernacular Brechtianism legible throughout all of Watkins’ work. One characteristic of this is the use of devices that break the smoothness and flow of traditionally coherent and legible dramatic space (direct address to camera by characters, expository or information-heavy narration on the soundtrack, deliberate anachronism). Another is a critique of the media apparatus into which individual audio-visual works are slotted (in his writing Watkins would label this ‘the Monoform’), analogous to Brecht’s demand, which he shared with Walter Benjamin, to not merely make work for the apparatus but to try to transform the latter. A third is the insistence that to show what is hidden and reified, and to politically affect the audience, ‘something has to be constructed’ (as Brecht put it in his famous remarks on the photograph of the Krupps factory), an insistence seen in Watkins’ films’ recurring enactment of scenarios – notably nuclear war, but also more implausible types of gamified punishment and military spectacle – set in the very near future, extrapolating the potentials of the present to try to make things more apprehensible.

Significantly, though, there was never any substantial discussion of Watkins’ films within the parallel engagement with Brecht in the Marxist film theory developed through the 1970s in the British journal Screen. Whereas Screen’s elaborations were dense theoretical edifices that linked Brecht to psychoanalysis and textuality in French writers like Jacques Lacan and Roland Barthes, Watkins’ films and writings are autodidactic and straightforward in tone. And whereas Screen favoured avant-garde modes, Watkins, up to the 1970s, at least, preferred to refunction popular televisual and feature-film formats – in the same interview cited above, for example, Watkins responds to a question about the influence of Dziga Vertov by saying, ‘I don’t have those sorts of influences’.[3] These facts, as well as his having left the UK and his tendency to work with comparatively bigger budgets and more professionalised institutions and companies, also help to explain the lack of connection between Watkins and the extensive radical independent cinema that existed in 1970s Britain under the name ‘counter-cinema’.

However, in the 1970s a shift is perceptible in Watkins’ cinema, dividing the early films up to Punishment Park from the later ones beginning with The Journey (1987), with the sequence from Edvard Munch (1974) to Evening Land (1977) as a transitional moment in between. This transitional moment coincided with Watkins teaching a seminar on television news programmes at Columbia University in New York in which he came to his notion of ‘the Monoform’, ‘the uniform and repetitive language-form which frames almost the entire output of the MAVM [mass audio-visual media]’.[4] (Again, the parallels with and differences from Screen are striking: Watkins’s claim for a singular form characteristic both of Hollywood fiction film and mainstream documentary form evokes Screen’s deployment of the notion of ‘the classical realist text’ to cover similar ground.)

With Edvard Munch, nearly four hours long in its two-part TV version, Watkins was beginning to stretch the standard cinematic and television format. The film inscribes the painter into the social and political context of late nineteenth-century Christiania (present-day Oslo) and Berlin at length, focusing on the tensions between the traditional bourgeoisie and its bohemian counterculture, and on the rise of feminism. Watkins would return to this period in later films: in his biography of another Scandinavian artist, the writer August Strindberg, in The Freethinker (1994), and in La Commune (2000). One might speculate that the importance of this period for Watkins relates to the rise of leftist and mass political movements – socialism, anarchism, feminism – and of the mass media.

After Evening Land, Watkins’ rate of production slowed in terms of number of films, but the films themselves grew lengthier, more challenging and more interesting. The Journey was fourteen and a half hours long, divided into nineteen approximately 45-minute episodes. The topic of The Journey is the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the possibility of nuclear war. In tracing this, the film attempts to be truly global in the voices it includes, reproducing extensive interviews with families and groups of people in Norway, Scotland, Germany, the Soviet Union, Algeria, Mozambique, the USA, Mexico, Japan, Tahiti and Australia. The globe is recurringly thematised too in the maps and animated visuals of television news that The Journey samples. Watkins’ voiceover at the beginning states that one of the film’s aims is to be an analysis of ‘the systems that deprive us of information and participation’. If nuclear war seemed to provide the absolute of secrecy and popular disempowerment, The Journey, by contrast, sought to provide information and to foster participation: by incorporating the voices of ‘ordinary people’, by getting these people to participate in staging scenarios of what might happen to them in the event of nuclear war, and, in remarkable scenes towards the end of the film, in creating global audio-visual connections not relayed through media corporations between these people, as the filmmakers get them to record messages to one another that they then play to them.

The critique of news media’s presentation of current events is a major part of The Journey, providing an extensive demonstration of what Watkins understood by the Monoform, the ‘rapid flow of changing images or scenes, constant camera movement, and dense layers of sound’,[5] that ‘gives no time for interaction, reflection or questioning’.[6] At the same time, Watkins’ faith in the power of other images to generate political effects, namely the enlarged images of the aftermath of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is a little surprising. From a later historical moment, one in which images of atrocity are easy to access, one might well be more sceptical about the value of this, as one might also be of the instrumentalising use the film makes of images of Ethiopian famine, which seems to draw from the same playbook as charity appeals. There is also something oddly quantitative about the comparisons Watkins makes between spending on nuclear weapons and other things this money could be spent on, which tends to circumvent an analysis of the structures that explain why money is spent in certain areas and not others.

The Freethinker, from 1994, is like Edvard Munch but more formally experimental, shifting back and forth in time in Strindberg’s life, and between this and stagings of his plays, Watkins and others’ preparation of these stagings, and audience discussion. The Strindberg film had begun in a similar way to the one on Munch, with Watkins preparing a script with the help of academics in the late 1970s, before shelving the project and reworking it collaboratively in the 1990s with a group of more than twenty students at an adult education centre.[7] The way the film’s elements reverberate with one another raises reflexive questions about the status of documents (Strindberg’s plays, diary entries, photographs, the remarks of others, and so on), about what can be known from them and what must be imagined or speculated. The filmmaker’s ‘theatrical’ turn continues in La Commune. This turn is perhaps best characterised as an attempt to mark out a distance from the televisual and cinematic apparatuses in order to counter them. Both The Freethinker and La Commune construct complex, non-historicist temporalities – the multiple chronologies of history in the former, the revolutionary time of the Paris Commune in the latter. Again, this seems to be a counter to the Monoform, which Watkins likened to ‘a time-and-space grid clamped down over all the various elements of any film or TV programme’, its method of the ‘universal clock’ dictating the standardised length of all aspects.

With his last film La Commune, Watkins seemed to have rediscovered Brecht’s Lehrstücke (learning plays). With over 200 actors and non-professional participants, developing their own characters and improvising scenes together, Watkins restaged and filmed the entire Paris Commune over a period of three weeks. La Commune is the summit of the increasingly participatory nature of Watkins’ work since at least Evening Land, in which scenes were improvised by the cast incorporating their own political opinions. Interviews with the participants in La Commune suggest that for many of them this event had a genuinely transformative effect on how they understood the world and themselves.[8] Watkins’ films had moved from critiquing the media to staging an alternative as well – to ‘staging the people’, to use the title of Jacques Rancière’s book on the culture of nineteenth-century French workers.

As a theorist, some of Watkins’ arguments and insights hold, particularly regarding the lamentable state of media education. Nevertheless, he compares unfavourably to some other theorists of the left who addressed the same topics. Serge Daney’s account of ‘the visual’ (as opposed to ‘the image’) developed in the early 1990s parallels Watkins’s Monoform. Daney describes ‘the visual’ as ‘the optical verification of a purely technical operation’ and as ‘the world seen from the viewpoint of power’, adding that the visual ‘is only One’. Significantly, both found the Gulf War a confirmation and illustration of their arguments (Daney in ‘Montage Obligatory’, Watkins in his film The Media Project, both from 1991). Yet Daney’s concept is the more supple and evocative. Similarly, Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s argument in his 1970 essay ‘Constituents of a Theory of the Media’ targets ‘the consciousness-shaping industry’ of monopoly capitalism in the name of the possibility of a social learning process in which participation in media production is democratised.[9] But Enzensberger’s more theoretically aware, explicitly Brechtian and Benjaminian arguments lead him to frame this through a classically Marxist distinction between the productive forces of the media and the capitalist social relations that fetter them, part of an account that is both more materialist and more nuanced. Indeed, Watkins would probably fall under Enzensberger’s criticism of oversimplified accounts of media ‘manipulation’ and concomitant ‘moral indignation’.

In remembering Watkins and his legacy, we would do well to relinquish the tendency to romanticise or exceptionalise him as a lone figure struggling against the system, in part by comparing him to other filmmakers. We might take for this comparative exercise someone like Robert Kramer, yet despite the parallels one might see between Ice (1970) and, say, Punishment Park, Kramer’s background in the US New Left and the militant collective Newsreel conditions a quite different tone to his films. Or even Jean-Luc Godard, who like Watkins was involved from the 1970s onwards in a relentless critique of television, which provided something like a necessary adversary in order to make work, but who undertook a much more experimental analysis of images and sounds in themselves. There is in the end something quite singular about Watkins’ trajectory and films. He leaves behind a remarkable corpus that remains in many aspects still to be worked through.

[1] German A. Duarte, Conversaciones con Peter Watkins / Conversations with Peter Watkins (Utadeo, 2016), 127.

[2] See John Cook, ‘The War Game’, in the booklet accompanying the BFI DVD/Blu-Ray of Culloden/The War Game, 8-14.

[3] Duarte, Conversaciones con Peter Watkins / Conversations with Peter Watkins, 121-122.

[4] Peter Watkins, ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’, Sabzian, available from: https://www.sabzian.be/text/the-dark-side-of-the-moon.

[5] Watkins, ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’.

[6] Peter Watkins, Notes on the Media Crisis (MACBA, 2010).

[7] Eva-Kristin Winter, ‘A Brief Introduction to The Freethinker’, in Marie Kloos, Marcin Malaszczak and Kristofer Woods (eds.), Future Revolutions: New Perspectives on Peter Watkins (Wolf Kino / Pogobooks Verlag, 2018).

[8] See the footage from the set and interviews with participants in the documentary film The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins (Geoff Bowie, 2001).

[9] Hans Magnus Enzensberger, ‘Constituents of a Theory of the Media’, New Left Review, I/64 (Nov/Dec 1970), 14.