Spectacular society

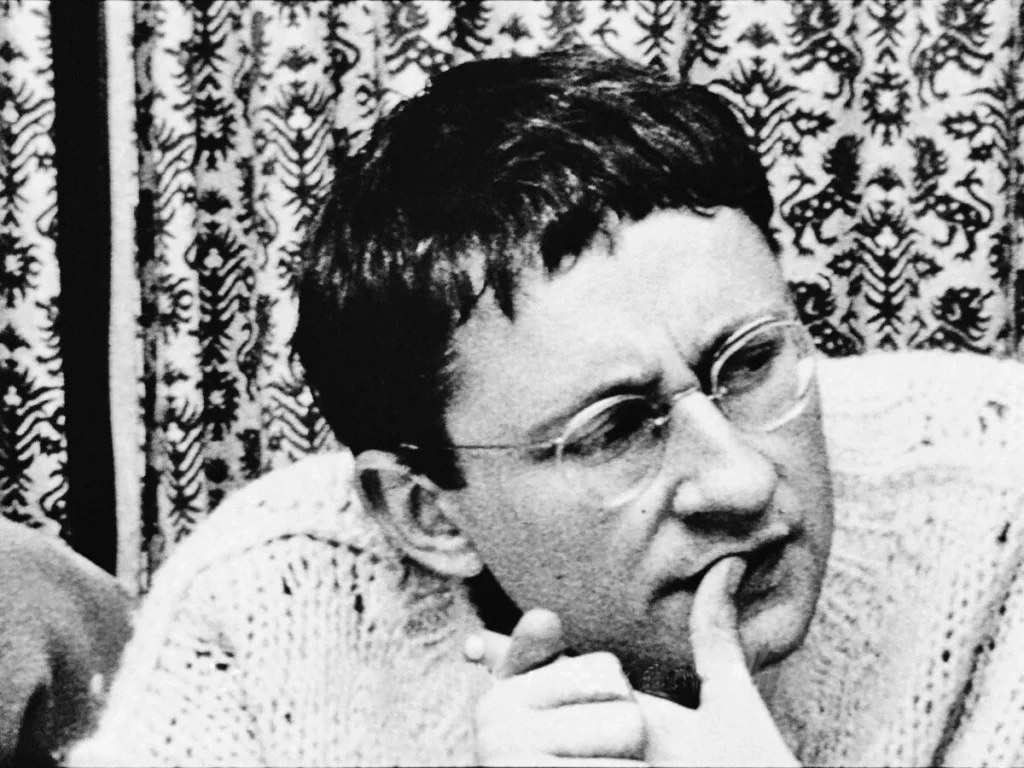

The Society of the Spectacle was written, as Guy Debord once put it, ‘with the deliberate intention of doing harm to spectacular society’.[1] It is somewhat ironic, then, that it has become such an established landmark within the culture that it sought to attack: nearly sixty years after its first publication in 1967, Debord’s book is now often mentioned in newspaper articles, lecture halls and cultural commentary. Its prominence has, however, been facilitated by a rather reductive view of its central claims. It is often assumed that the book’s central concept of ‘spectacle’ denotes the visual imagery of capitalist culture, and thus the great mass of shopfronts, screens and entertainments that mark contemporary social life. Understood in these terms, the book can then serve as a useful reference point in commentary on such phenomena; hence its prominence. Yet such a reading simply cannot accommodate all that Debord says in the book, rendering his theory opaque. Moreover: if spectacle simply means visual imagery, we have little sense of how and why it might be connected to his avowed revolutionary politics. On such a reading, then, the book’s purportedly harmful intentions and meaning can slip from view.

I do not mean to deny that Debord’s book addresses the visual and mass-media phenomena with which it is often identified. Thesis #6 of The Society of the Spectacle explicitly casts ‘news, propaganda, advertising, entertainment’ as ‘particular manifestations’ of spectacular society. But the fact remains that, whilst they are certainly part of the problematic that the book addresses, they are, nonetheless, only one aspect of it. And, as Debord states at the very outset of his book, in Thesis #5, one cannot grasp that whole problematic by focussing on only one of its elements: ‘The spectacle cannot be understood’, he states there, ‘as a mere visual excess produced by mass-media technologies’. This point is reinforced by Thesis #24, which describes ‘the “mass media”’ as only the spectacle’s ‘most glaringly superficial manifestation’. There is, then, clearly more going on than a simple diatribe about modern visual culture.

On the reading that I outline here, Debord’s theory of spectacle is best understood as a critique of the separation of social power from its producers. It is an account of a society that has become effectively separated from its own historical agency, due to the degree to which its collective powers have become bound up with the operation and agenda of an effectively autonomous economy. We are ‘spectators’, for Debord, not just of too many screens and images, but of an entire form of social life that escapes our collective control; and, in his view, that state of affairs could only be superseded through total, transformative, revolutionary social change (hence the sense in which the book was committed, to quote Debord’s remark again, to ‘doing harm to spectacular society’).

In what follow below, I try to provide what I hope to be an accessible introduction to these aspects of the book. As is now increasingly acknowledged, the book is steeped in Hegel, Marx and related material, and a full reading of the text requires some engagement with these and other such sources.[2] But I shall try to set out only the bare bones of those ideas here, and, when making my points, I shall refer to specific theses in the text. (I have provided links to the relevant chapters of Knabb’s translation, although I would encourage interested readers to compare it with the two others: the Perlman translation is closer to the original French, and the Nicholson-Smith version is perhaps the best English rendition; Knabb’s is, however, more readable and readily accessible online.) But, although I shall try to keep Hegel, Marx and other philosophical sources in check, I will, nonetheless, put considerable emphasis on what I take to be the central element of this book, and indeed of Debord’s broader oeuvre: namely, his concern with temporality. The theory of spectacle, I hope to show, is fundamentally concerned with time, and with what we do in it.

I begin by outlining the concept of spectacle, and the way in which the book’s critical diagnoses of modern society relate to Debord’s highly politicised understanding of temporality. Having done so, I then look briefly at the book’s initial reception, before setting out a short overview of the origins and development of the ideas that the book presents. That will involve looking at the roots of those ideas in Debord’s early avant-garde concerns; at the formation and development of the Situationist International (SI); and at Debord’s developing engagements with Marx and Hegel. I then return to The Society of the Spectacle, and comment on the book’s content and structure. I close with some short remarks about its legacy, and about the ways in which it might be assessed today.

Subject and objects

The word ‘spectacle’, with its connotations of show, display and entertainment, evokes a relation between image and observer. It suggests a relation in which that which is observed is active, and perhaps mesmerising and captivating, and in which the observing subject is comparatively passive and receptive. This certainly pertains to the visual imagery with which the book is now commonly associated, but we can get closer to Debord’s intended meaning if we think of that relation more broadly and metaphorically. The idea’s roots lie in his early concern that such a dynamic was at work in the contemplation of art objects. Debord was engaged in avant-garde culture, and with surrealism in particular, from an early age, and the avant-garde motif of uniting art and life runs throughout the course of his work. At its outset, the relation between a passive observer or audience member, confronted by a separate, entrancing object or performance, exemplified art’s separation from life, and his early notion of the construction of ‘situations’ was intended to remedy that separation. Situations would be moments of lived experience, constructed and lived as artistic creations. But these early ideas developed, during the late 1950s, into the view that modern life as a whole had become marked by that same dynamic of separation. And, as the theory of spectacle took form in the 1960s, the relation between a passive human subject and a comparatively active object of contemplation was taken to exemplify the defining problem of modern society as a whole: namely, the emergence of a form of social life so alienated from its producers and participants as to seem like a separated and independent object of ‘contemplation’.

Perhaps the easiest way to approach this is via Debord’s debts to Feuerbach, whose critique of religion influenced the young Marx, and which provides the epigraph to Debord’s first chapter). In religion, for Feuerbach, we project our own collective powers and capacities into an imaginary heaven, and worship them in the form of a fictitious God. Marx later contended that a similar condition was at work in capitalist social relations: ‘Just as man is governed, in religion, by the products of his own brain,’ he wrote, ‘so, in capitalist production, he is governed by the products of his own hand’.[3] Debord concurred, but he framed this as a problem that now extends far beyond the factory walls, and throughout the fabric of social life. According to Thesis #20, ‘The illusory paradise representing a total denial of earthly life is no longer projected into the heavens, it is embedded in earthly life itself.’ The Feuerbachian problem of human agents bowing down to their own creations now applied not just to religious constructions, but to an entire mode of social life.

Debord drew very heavily indeed on Marx’s early writings when composing The Society of the Spectacle (as he noted in his correspondence, almost all the references and extracts from Marx employed in the book come from works that Marx produced between 1843-6),[4] but his general understanding of this problem of submissive separation comes from Marx’s later account of fetishism in Capital. To sketch this very briefly: Marx described the subordination of human subjects to the economic objects that they create, and the ways in which capitalist social relations involve attributing characteristics to those objects that stem from the social activity of their producers. Outside of those social relations, money and commodities are mere things. But, within capitalist social relations, they become accorded, and animated by, a form of value that derives from the social actions and interactions of their producers and users. They then take on a degree of independent power from their producers, insofar as their movement on the market shapes the actions and interactions of the human subjects that create, pursue, and consume them. And, because their movement is driven by capital – and because capital, for Marx, derives from the productive activity of human subjects – the result is a mode of social organisation in which human agents become separated from, entranced by, and subordinate to, the effectively independent operation of their own estranged collective powers.

Debord held that capitalism’s development, since Marx’s day, had massively extended this problematic of separation, subordination and appearance. The Society of the Spectacle claims that modern society has become divorced from its ability to shape and determine its own historical existence (i.e. its existence in time) due to the extent to which individual and social life has become governed by the dictates of its own quasi-autonomous economy. The book’s visual terminology – and thus the dynamic between passive observer and active image that I sketched above – was used to capture that condition. But it may be worth underscoring that he was not, then, attempting to present a detailed socio-economic analysis. Instead, Debord’s book uses its visual terminology to grasp and give voice to the broad existential problematic that he believed marked modern society as a whole – i.e. the condition of generalised separation sketched here – and to articulate the frustrations, and the revolutionary demands, to which that problematic gave rise. The book presents a form of life that has become so alienated from its producers and participants as to appear somehow other to them, and in doing so, it sets out what Debord took to be the stakes of the modern revolutionary project.

This allowed from some rather loose vocabulary; for the use of the full range of his visual terminologies’ connotations and meanings, and for its extraordinarily widespread and all-encompassing application. As we have seen, it does indeed relate to the adverts, fads and fashions of the modern world. But it also refers to a very wide range of further social phenomena that engender obeisance, emulation or desire in ways that suit the perpetuation of the existing capitalist status quo. Debord and the SI described a whole host of different things as ‘spectacular’: religion, dogma, hierarchical and institutional roles, forms of political leadership, etc., were all cast in these terms. These things are certainly disparate; yet as Debord put it in Thesis #10, ‘The concept of spectacle interrelates and explains a wide range of seemingly unconnected phenomena’. They are connected, in his view, insofar as all could be construed as forms of separated social power (the leader, the dogma, the celebrity – all possess power only insofar as they are accorded it by their adherents), and together, they compose the spectacle’s ‘images’. Like ideological constructs, they foster patterns of activity and interaction that suit the current order of things; but unlike a traditional notion of ideology, they are not merely mental or ideal, because they take concrete form in a host of different structures and practices (see, for example, Thesis #212). And through internalising and actualising the norms that they express, concrete social life itself thereby becomes a mere ‘representation’ of the self-determinacy and existential fulfilment that they fallaciously proffer and promote.

Debord’s central claim, then, is that we have become ‘spectators’ not just of a world full of TV screens and visual imagery, but of a mode of social life governed by our own alienated activity. We are alienated passengers, in his view, within a form of social life that we create, interact within, and perpetuate, but which moves and operates according to its own effectively independent agenda; dazzled ‘spectators’ of a kind of collective performance, albeit a performance in which we ourselves act (see Theses #30-1).

Spectacle and temporality

The predicament that this posed could only be resolved, according to Debord, through the supersession of the social structures that compose this flawed way of life. And that, in his view, required revolutionary social change. The latter point deserves to be underscored, given the intense scorn that Debord heaped on readers who failed to acknowledge it,[5] and given also the extent to which his politics has become treated as a kind of optional extra appended to the theory. As I have stated, the concept of spectacle was meant to serve as a means of defining the stakes of the modern revolutionary project. And, when the latter is cast in these terms, it changes: in place of a demand for fairer working conditions, or for more equitable distribution, it became a much more extreme demand for direct, collective, self-determinate control over the conduct of social life, and for the flourishing of lived experience as a whole. His early vision of superseding the separation of art from life through the construction of situations had thus given rise to a new, ludic and fiercely utopian vision of communism. The latter’s actualisation, and the demise of spectacle, required that all forms of separated social power needed to be superseded. The target was not just the commodity and its derivatives, but all forms of hierarchy, political leadership, manipulation and dogma.

The book presents this demand via a focus on temporality. It contains two entire chapters on time, and references to time, history and temporal experience can be found throughout its theses (see, in particular, Thesis #158). Remarkably, this emphasis on temporality is almost entirely absent from much of the literature and commentary on Debord’s theory. But time is, nonetheless, central to the book’s claims. In his view, the material poverty that had exercised previous revolutionary demands had been absorbed into a more existential form of poverty, due to modern society’s denigration of its inhabitants’ ability to direct their own lived time, and due to the general demise of this society’s ability to consciously and collectively direct its own future. The revolution that the book advocates (and which, we should remember, it purported to herald) is thus a new mode of communism in which collective control would be taken not just of the means of providing for society’s material needs, but of the means of shaping lived time itself. Thesis #163 speaks of the ‘temporal realisation of authentic communism’; likewise, Thesis #200, which alludes to The Communist Manifesto, declares that ‘history itself haunts modern society like a spectre’.

Debord saw this as the present face of an old project. Indeed, he saw both the spectacle and its potential revolutionary resolution as contemporary versions of longstanding dynamics. The modern spectacle was simply a new, more extreme form of a tendency towards separated social power that had inhered throughout the societies of the past. For example, in a letter of 1971, he wrote:

[The spectacle] has its basis in Greek thought; it increased towards the Renaissance (with capitalist thought); and still more in the 18th century, when one opened museum collections to the public; it appeared under its completed form around 1914–1920 (with the propaganda [bourrage de crâne] of the war and the collapse of the workers’ movement).[6]

The problem of separated powers, and the related issues of control over history and revolt, extend far back into the past (indeed, Thesis #25 states that ‘all separate power has been spectacular’). Modern consumer capitalism had merely brought these issues to the fore, obliging the revolutionary workers’ movement to recognise and confront them with new clarity: hence his claim in Thesis #143 that ‘By demanding to live the historical time it produces, the proletariat discovers the simple, unforgettable core of its revolutionary project’. Modern society’s existential poverty, in other words, had foregrounded and clarified a demand for free, self-determinate control over lived time that had inhered throughout the struggles and demands of the past.

This broadly Hegelian picture of the modern revolution, according to which spectacular society brings a deep, longstanding historical problematic to light within Debord’s present, is supported by the extraordinarily ambitious philosophy of history set out in the book’s fifth chapter, and by the history of the 19th and 20th century workers’ movements set out in its fourth chapter (and, to a lesser extent, by the history of culture presented in its eighth chapter).

The central idea here, for Debord, is that different social formations have afforded their inhabitants differing degrees of power to shape their own existence in time, and thus to govern their own history. But these social formations have also been marked by differing degrees of access to such power. The general trajectory described in the book’s fifth chapter is one in which that power has grown over the course of human history in tandem with its increasing separation from its producers. This had led towards a purportedly explosive extreme in Debord’s present (note that chapter one is titled ‘Separation Perfected [achevée]’), and it was held to have shaped the workers’ movements stumbles and failures towards the realisation that nothing short of total, direct, collectively self-determinate control over lived time would suffice.

Debord’s account of this trajectory begins in Chapter Five with the very earliest human societies. He describes them as having been shaped by nature and the seasons, and were thus marked by a ‘cyclic’ experience of time (see Theses #126-7). Yet later social formations gradually produced an increased sense of time as historical and ‘irreversible’. Their economic organisation enabled the liberation of some sections of society from agrarian toil, and their culture and technological capacities fostered greater capacities to conceive and conduct change in time (see Theses #128-9). The control of this increased power to shape historical change was, however, the preserve of the masters of those societies, and it remained removed from those whose social activity enabled it. Debord then contends that the advent of capitalist society deepened this separation. Industrial capitalism produced a newfound awareness of the potential mutability of the world and society, but it also meant that control over the capacity to conduct such change became further separated from its producers, and relegated to an increasingly sovereign economy (see Thesis 143: ‘The bourgeoisie has … made historical time known and has imposed it on society, but it has prevented society from using it’; see also Theses #144-6). Chapter Four describes the workers’ movement’s growing drive towards rectifying that state of affairs. It begins with Hegel’s philosophical account of historical change, presenting the latter as a flawed but no less crucial insight into humanity’s historical existence, and then moves to Marx’s critique of capitalism: ‘Marx’s project’, Debord writes, in Thesis #80, was ‘a project of conscious history’. The chapter then details the workers’ movement’s development and mistakes, contending that this had led it, within his present, to a position and predicament wherein the need to supersede all forms of spectacle could be clearly seen. All revolutionary figureheads and leaders now needed to be rejected, for as Thesis #122 puts it, ‘revolutionary organisation has had to learn that it can no longer combat alienation with alienated forms of struggle’. The result, in effect, is a peculiarly militant form of collectivist anarchism (to be organised initially, for Debord, through workers’ councils: see Theses #116-19).

The concept of spectacle, then, concerns time, or rather what we do in time. It was meant to capture a condition of separation from control over own lived time, and the consequent demand to rectify that separation (note the quotations from Shakespeare and Gracián used for the epigraphs to the book’s fifth and sixth chapters). And time, moreover, connects the concept of spectacle to Debord’s utterly uncompromising revolutionary politics. If this is neglected, and the book reduced to a description of a mode of social life swamped by visual imagery, its political commitments can fall from view (Debord, we might note, actually predicted such readings within the book itself: Thesis #203 observes that ‘The critical concept of “the spectacle” can’, if divorced from revolutionary praxis, ‘undoubtedly be turned into one more hollow formula of sociologico-political rhetoric used to explain and denounce everything in the abstract, thus serving to reinforce the spectacular system’).

The initial reception of The Society of the Spectacle

It may be useful to note that The Society of the Spectacle was once viewed with genuine alarm, and that the ideas advanced by the Situationist International (SI) – the radical group that Debord helped to found in 1957, and with which he and his book are closely associated – were once considered a genuine threat. In 1966, the year before The Society of the Spectacle was published, a group of radical students managed to get elected to the University of Strasbourg’s student union. They used the entirety of its funds to print 10,000 copies of a situationist text titled ‘On the Poverty of Student Life: Considered in its Economic, Political, Psychological, Sexual and Especially Intellectual Aspects, with a Modest Proposal for Doing Away with It’. The resultant scandal prompted horrified outrage: according to the judge who presided over the union’s subsequent closure, the text promoted the rejection of ‘all morality and legal restraint’, ‘theft, the destruction of scholarship, the abolition of work, total subversion and a permanent worldwide proletarian revolution with “unrestrained pleasure” as its only goal’[7] (he was not altogether wrong). Consequently, when The Society of the Spectacle was first published in November 1967, the notion that something called ‘situationism’ might pose some kind of dangerous, violent, and yet oddly hedonistic threat to modern society was already in the air.[8]

The Society of the Spectacle was followed only one month later by another situationist book, The Revolution of Everyday Life, which was written by Raoul Vaneigem, the SI’s other principal theorist (its French title is a little different: Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations). Due to the growing interest in situationist ideas, both books were reviewed in the popular press. They received a mixture of cautious praise, contempt, and worry, and were presented as significant examples of the burgeoning protest movements of the time. The Times Literary Supplement went so far as to describe The Society of the Spectacle and The Revolution of Everyday Life, respectively, as ‘the Capital and What Is to Be Done, as it were, of the new movement’; Le Monde spoke of the ‘negative and provocative violence’ of the two books’ tone and demands, and remarked that their extravagant hostility ‘staggers thought’, and made reading them ‘disagreeable’; The New York Times observed that, for Debord, ‘One has to destroy all authority, especially that of the state, to negate all moral restrictions, to expose fossilised knowledge and all “establishments”.’[9] This rection was reinforced only a few months later when Paris was shaken by the uprisings of May 1968. Situationist-inspired slogans were daubed across the Latin Quarter, and the SI’s ideas, literature and status gained further prominence (Debord and the SI quickly cast the May uprisings as confirmation of their view that modern society was pregnant with revolutionary potential).[10]

At the time of its first publication, then, The Society of the Spectacle was clearly linked to social unrest. It was viewed by its author, its admirers, and its worried critics alike as an articulation of the frustrations and demands of an emergent revolutionary project. And, as far as Debord was concerned, it had considerable success in that regard. As he later remarked, ‘Many [books] are not even opened; few are copied on to walls’.[11]

The unification of art and life

Having now outlined the book’s central ideas, and indicated its intended militancy, we can try to shed a little more light on its contents by looking at the origins and development of its claims, and at the influences that informed it. And if we are to do that, it will prove useful to turn first to Debord’s early connections with avant-garde culture.

In 1951, when he was just 19 years old, Debord attended the Cannes film festival. Whilst there, he encountered Isidore Isou, the primary figure in a group called the Letterists. They were concerned with remedying what they took to be the stagnation of modern culture through artistic destruction, and Isou and other Letterists had attended the festival with the aim of promoting his deliberately provocative film Treatise on Slobber and Eternity. Debord, who was already keenly interested in Dada, surrealism and the avant-garde, was greatly impressed. He remained in contact with them after the festival ended and soon moved to Paris to join them.

Debord’s time with the Letterists informed his later views concerning the limitations and passivity of modern culture. But such views were clearly evidenced the following year, in his first film. 1952’s Howlings in Favour of Sade it consists only of an alternating black and white screen; it is silent when the screen is black, features only odd, fragmentary dialogue and statements when the screen turns white, and it ends with 24 minutes of complete silence. It was deliberately intended to aggravate the audience, and to test their capacities for boredom and mute acceptance. The concept of spectacle would not take form for another few years – it does not appear in his writings until around 1955 – but, at this early stage, Debord was already trying to attack and subvert forms of passive spectatorship. In the aftermath of the film, he and several other members of the Letterists split from Isou and formed a splinter group called the Letterist International (LI). They took a more radical perspective than Isou’s faction, lived a lifestyle marked by excess and petty crime, and developed some of the ideas that would later become firmly associated with the Situationist International. Unitary urbanism,[12] psychogeography,[13] the dérive[14] and détournement[15] all emerged at this time; and most importantly, so too did the constructed situation.

As indicated above, the constructed situation was an attempt to unite art and life: to employ the creative and transformative powers of art in the deliberate, ludic construction of enriched moments of lived experience. Art would be ‘realised’ in shaping the necessarily transitory moments of lived time, rather than in moulding the comparatively static forms proper to its traditional mediums (as Debord later put it: ‘we care nothing about the permanence of art or anything else’).[16] This was framed as an attempt to fulfil the promises of both Dada and surrealism. For Debord, Dada had gestured towards the collapse of art’s separation from lived experience, through its attacks on art’s staid institutions and norms, but it had contributed relatively little in terms of indicating what should replace it. Surrealism, on the other hand, had envisaged a transformation of everyday life, but it had done so whilst remaining within the bounds of the extant art world. The resultant position would later be succinctly expressed in Thesis #191 of The Society of the Spectacle:

Dadaism sought to abolish art without realising it; Surrealism sought to realise art without abolishing it. The critical position since developed by the Situationists has shown that the abolition and realisation of art are inseparable aspects of a single transcendence of art.

In the 1950s, however, these ideas were still taking form, and despite Debord’s extreme hostility to Sartre, Sartrean existentialism also played a role in shaping these views. Sartre had argued that our lives are composed of ‘situations’: contexts and predicaments that we find ourselves cast into, and within which we must choose and act. Yet, for Debord, rather than merely having such moments forced upon us by the standardised patterns of modern life, we ought instead to consciously shape moments of lived time. As he later put it: ‘A person’s life is a succession of fortuitous situations, and … the immense majority of them are so undifferentiated and so dull than they give a definite impression of sameness …We must try to construct situations’.[17] In his view, this was the next step to be taken by the avant-garde. These ideas developed during mid-1950s, and became tied to the view that the revolutionary workers’ movement could bring about such a state of affairs. The position that emerged – a position that would later develop into the claims set out in chapters four, five and eight of The Society of the Spectacle – can be sketched as follows.

Debord held that the early decades of the twentieth century had harboured the potential for an entirely new form of social life: one in which art and the everyday might fuse. This possibility was afforded by the potential conjunction, at that time, of the revolutionary workers’ movement and avant-garde art. The workers’ movement was a growing power, and it was demanding more from life; avant-garde art, meanwhile, was attacking the norms and institutions of the extant art world, and whilst moving ever further away from functioning as a means of representing life, it was also gesturing, in surrealism, towards ways of enriching and refiguring life itself. This moment of potential was, however, missed: the workers’ movement succumbed to hierarchy and authority, art degenerated into the empty repetition of familiar forms, and the commodity triumphed (this set of ideas lies at the root of Debord’s later contentions that the emergence of a fully spectacular society could be dated back to the start of the twentieth century). This led to the view that, for culture to advance to a new stage, and to thereby realise the potential that it harboured, grand social change was required; and in the absence of revolution – caused, in part, by the workers’ movements subordination to the strictures of party and statist politics – culture had been stagnating. In the 1950s, then, Debord can be found remarking that the ‘retreat of revolutionary politics’ had caused the ‘movement of cultural discovery’ to culminate ‘around 1930’,[18] and that ‘the premises for revolution, on the cultural as well as the strictly political level, are not only ripe, they have begun to rot’.[19]

The Situationist International

These ideas informed Debord’s seminal 1957 ‘Report on the Construction of Situations’: a text that begins by stating that ‘First of all, we think the world must be changed’, and which goes on to argue for the need to research and advance possibilities for an entirely new mode of social life, centred around the creative enrichment of lived time. The ‘Report’ was written in preparation for what would become the Situationist International’s inaugural conference. In 1956, Debord and other members of the LI had met with figures from other European avant-garde groups in the Italian town of Alba, on the grounds that they were all moving in broadly similar directions. A subsequent meeting was then held the following year in Cosio d’Aroscia, also in Italy, and Debord’s ‘Report’ was presented to the attendees. It became the fledgling Situationist International’s founding document.

The ‘Report’ would remain a major landmark, but many of the positions set out within it would later be developed and altered. Two are of particular significance. Firstly, the ‘Report’ contains some rather brief and enigmatic references to ‘spectacle’, and it even contends, suggestively, that ‘The construction of situations begins beyond the modern collapse of the notion of spectacle’.[20] At this stage, Debord seems to be thinking about ‘spectacle’ chiefly in terms of culture, and he appears to have been thinking about culture in the relatively narrow sense of the consumption of art, literature, theatre, etc., rather than in terms of social life per se. Yet, even so, we can already see his developing view that culture, albeit in that narrow sense, had become characterised by the relation of a passive observer to a contemplated object. The ‘principle of the spectacle’, he writes in the ‘Report’, is ‘nonintervention’,[21] and whilst referencing Brecht, he endorses cultural productions that have taken steps towards challenging this relationship (we should recall here his own deliberately provocative first film). But this too would soon start to change into a focus on the separation of social agents from social life itself.

The late 1950s and early 1960s would also see a changed understanding of the nature and role of the SI itself. The ‘Report’ reflects the SI’s initial conception of the group’s then broadly art-oriented activity as a form of research into the kind of self-determinate comportment that revolution would enable within a future society. By devoting itself to experimenting with the construction of situations, the SI would work out the possibilities of the new form of social life that revolution would create. But, by the early 1960s, Debord had come to the view that the SI needed to focus on fomenting and facilitating that revolution. The group became concerned with critical social theory, rather than the analysis of art and culture, and with revolutionary organisation rather than prefigurative cultural research. The group thereby quickly evolved out of its initial avant-garde origins into a much more militant political organisation.

Debord produced two more films following the SI’s inception in 1957, and in both we can see his later ideas starting to take form. 1959’s On the Passage of a Few Persons Through a Rather Brief Moment of Time endeavoured to expresses the limitations of modern life in general, and declared that Debord’s ‘era had attained a level of knowledge and technologies that made possible, and increasingly necessary, a direct construction of all the aspects of a mentally and materially liberated way of life [d’une existence affective et pratique libérée]’.[22] In 1961, he produced Critique of Separation: a film that also sought to give cinematic expression to the flawed nature of modern life, and which foregrounded the concern with autonomy that would become crucial to his mature theory of spectacle. The film complains that ‘we are unable to make our own history, to freely create situations’,[23] and it holds that ‘The point is not to recognise that some people live more or less poorly than others, but that we all live in ways that are out of our control’.[24]

The turn to Hegelian Marxism

That statement from Critique of Separation reflects an important development and shift of emphasis. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Debord started to engage in more detail with Hegelian and Marxian ideas. Marx’s early writings were of particular significance here (principally, the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 and The German Ideology). So too was a peculiarly French interpretation of Hegel, which framed the latter’s philosophy as advancing a flawed but indispensable insight into the conflictual and dynamic movement of social life and historical change.

This combination of influences informs the conception of human subjects that would later be employed in The Society of the Spectacle. The account of history and temporality outlined in the sections above depends on a particular view of human existence. For Debord, we are social and historical creatures: we change ourselves and our world through social activity as we pass through time, and we do so in ways that are shaped, enabled and restricted by the mutable social formations within which we reside and act (see, for example, Thesis #125, which alludes to Marx’s Manuscripts and which begins with a quotation from Hegel; see also Thesis #161). This view of human existence – as temporal, mutable, socially articulated, and as thus potentially self-determining and self-creating – underpins the account of human history described earlier.

Debord’s adoption of Hegelian Marxist ideas was also shaped by his engagement with several influential figures. The first that might be mentioned here is Cornelius Castoriadis, who was the primary figure within Socialisme ou Barbarie, a group with which Debord was very briefly affiliated between 1960 and 1961. Debord would come to regard Castoriadis with considerable scorn, but the latter’s ideas chimed with his developing view that revolutionary contestation in an affluent consumer society should not be reductively centred material impoverishment and the wage-relation, as in traditional Marxism, but should be seen as a struggle between those who want more from life, and those prepared to accept its current forms. Debord and the situationists were moving towards the view that would later inform The Society of the Spectacle: namely, that the ‘new’, modern proletariat were all those who had been separated from the means of shaping their own lives: all those who, ‘regardless of variation in their degree of affluence’,[25] have ‘no possibility of altering the social space-time that society allots to them’.[26] This effectively class-less social class was enormous (Thesis #26 of The Society of the Spectacle would contends that the predicament of spectacle ‘proletarianizes the world’), and its demand for life’s enrichment was held to be potentially more extreme than any mere push towards more tolerable working conditions and more equitable distribution (see Thesis #114, and the utopian goals expressed by the situationists more broadly).

Henri Lefebvre was another significant figure. For Lefebvre, everyday life was a topic of supreme and yet overlooked importance, and the first volume of Lefebvre’s Critique of Everyday Life, published in 1947, would no doubt have been read by the young Debord. Lefebvre’s ideas included the view that the contemporary banality, alienation and boredom of the everyday were punctuated by ‘moments’ of intensity and passion that threw its inadequacies into sharper relief. Debord and the S.I. recognised the affinities between these ideas and their own, and a short-lived friendship was established. Their relationship with the SI broke down in 1962 over mutual accusations of plagiarism, but it was clearly a productive exchange for both parties. In 1961, Lefebvre published the second volume of his Critique, which echoed many of the SI’s concerns; that same year, Debord presented a talk (delivered via a tape recorder in a suitcase) to Lefebvre’s Group for Research on Everyday Life titled ‘Perspectives for Conscious Changes in Everyday Life’. The talk includes the following lines, which neatly prefigured the basic premise of The Society of the Spectacle:

History (the transformation of reality) cannot presently be used in everyday life because the people who live that everyday life are the product of a history over which they have no control. It is of course they themselves who make this history, but they do not make it freely or consciously.[27]

The notion of separation from history, described above, was thus taking form. Its development at this time also owed a great deal to Georg Lukács’ History and Class Consciousness of 1923. Lukács’ book exerted a great influence on Debord’s thought, albeit a largely unacknowledged one (the only reference to Lukács in The Society of the Spectacle is a damning critique in Thesis #112). Many of the quotations from Hegel and Marx that Debord would use in his book also appear in History and Class Consciousness[28]– they may well have been lifted from its pages – and Lukács’ Marxian re-working of Hegelian ideas is fundamental to Debord’s basic contentions. For Lukács, the social world is shaped by human action, and the continuance of its current capitalist formations depends upon human agents continuing to behave in the ways required to perpetuate it. Yet, for Lukács – who also drew heavily on Marx’s theme of fetishism –, the capitalist social world seemed somehow independent, fixed, and indeed ‘natural’ or inevitable; an immutable ‘given’ to which we must adapt and accommodate ourselves. The proximity between Lukács’ book and Debord’s claims is striking: capitalist society, according to History and Class Consciousness, had become subordinate to its own economy, and human agents had taken up what he described as a merely ‘contemplative’ relation to their own social existence.[29] Lukács also held that the proletariat were in a position to recognise and respond to this dilemma. The nature of their circumstances would oblige them to recognise that they were, in fact, the creators of this society, and that they possessed the capacity to shape it anew. The objective social world was the result of their subjective historical agency, and, although the latter had become ensnared within the social relations of capitalism, the destruction of those social relations would liberate their capacity to shape their own objective existence freely, collectively and self-consciously. The echoes between this view and Debord’s ideas are, I hope, readily apparent (they are also significant on a more technical and philosophical level, insofar as Lukács’ use of Hegelian themes informed Debord’s own: the Lukácsian motif of subject-object unity is apparent, I think, in Theses #74, 116-7, and passim).

More generally, one of the most important themes that ought to be foregrounded in the development of Debord’s ideas during the early 1960s was that of the ‘realisation of philosophy’. In his early critical work on religion, Marx stressed that it was not enough for critical and philosophical thought to simply point out the illusory nature of religious dogmas. In addition, he held, one needed to address the flawed social conditions that lead people to find palliative comforts in such illusory promises, and to thereby provide those who would seek to change those conditions with the intellectual analyses of society that would enable them to do so. The philosophical critique of society, in other words, would become a real practical force, and in doing so, it would enable the proletariat to supersede their own proletarian condition (thus, ‘philosophy cannot realise itself without the supersession [Aufhebung] of the proletariat, and the proletariat cannot supersede itself within the realisation [Virwirklichung] of philosophy’).[30] This idea had a marked impact on Debord’s thought, and it greatly informs the overall project of The Society of the Spectacle. It inflects the book’s critique of all forms of detached, passive, intellectual contemplation, and the stress that it places on the need to actualise theory in concrete action (see, for example, Theses #19, 90, 191 and 203); more broadly, it also informs the book’s general argument for the actualisation of all forms of social power in transformative historical activity. Moreover, it shaped the development of the Situationist International itself.

In 1962, the SI underwent a major split. By this time, Debord had come to the view that, if the task was to alter society and culture, so as to enable an entirely new form of social life, then the role of a genuine avant-garde, within this context, must be to foment social revolution; and, if the extant art-world was part of the problem that needed to be addressed, continued engagement within the art-world could only be reactionary. The task now, he held, was to generate the critical social theory that would facilitate revolution. This resulted in a break with the primarily Scandinavian and German practising artists within the SI, and the initiation of a new stage in the group’s activities; one that would be centred revolution, as conceived via the concept of spectacle. The phrase used to encapsulate this development was that ‘The S.I. must now realise philosophy’.[31]

The Society of the Spectacle

The ideas that Debord developed during the 1950s were thus refined and given sharper and more Hegelian and Marxian inflections during the late 1950s and 1960s; and, in the wake of the split of 1962, the SI became increasingly militant, and increasingly concerned with revolutionary contestation. The Society of the Spectacle arose from this new, harder version of the SI, and it was intended to synthesise and express the ideas that Debord and the group had worked out by that time. Debord started writing it in 1965,[32] having decided that he wanted the Situationist International to have ‘a book of theory’ that would be ‘present in the troubles that were soon to come’, and which would also serve to pass the group’s ideas on ‘to the vast subversive sequel that these troubles could not fail to open up’.[33] And, in keeping with the theme of philosophy’s realisation in revolutionary praxis, the contribution that the book endeavoured to make was that of grasping, as clearly as possible, the fundamental core of modern revolution.

This then brings us back to the ideas that I outlined earlier. As we saw there, the concept of spectacle was devised as a means of grasping and viewing Debord’s entire historical moment from the perspective of imminent, explosive revolution. As we saw earlier, Debord points out in Thesis #10 that the book uses the concept to grasp a host of seemingly diverse aspects of social life as aspects of this one general and effectively all-encompassing problematic. The domination of lived time by the economy is held to have forced revolutionaries to grasp the deep, fundamental core of all prior revolutionary struggle – the demand to take free, conscious and collective control over life itself – and to thus reject all forms of subordination to separated social power. That rejection entailed opposition not only to the commodity and all that follows from it, but also to all forms of hierarchy, arbitrary authority, revolutionary figureheads, dogma and faith (as noted, and despite the critical remarks set out in Theses #92-4, the book’s overall stance is close to aspects of collectivist anarchism). The basic problem of spectacle is separated social power, and, although the ubiquity of the commodity-form had generated a social order that had brought that separation to an extreme, the book also warns against any further instance in which collectivities of social agents might become subordinate to concentrated expressions of their own collective power (hence the remarks set out in Theses #121-2). But, having now sketched out the book’s ideas and their origins, we might now look, albeit briefly, at its peculiar mode of presentation.

If The Society of the Spectacle simply described, prescribed, or otherwise merely represented opposition to spectacular society, it would amount to no more than a spectacular critique of the spectacle. So, rather than merely depicting the negation of modern culture within its pages, the book endeavours to actually instantiate that negation within the very form of the work itself.

Similar attempts to unify the form and content of cultural critique can be found throughout Debord’s oeuvre. One might think here of Debord and Jorn’s Mémoires, which was given a sandpaper cover, so that it would rip any book that it was stacked next to; of Debord’s declaration in his détourné film In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni that it ‘disdains the image-scraps of which it is composed’;[34] or, indeed, of his remark in Critique of Separation that its ‘poverty of means’ is ‘intended to reveal the scandalous poverty of the subject matter’,[35] i.e. the poverty of modern life. Needless to say, none of this makes these works very easy to understand. Yet Debord – an autodidact who had very little respect for modern universities, or for those who work within them – cultivated an air of almost aristocratic disdain for any such complaint. To quote In Girum once again: ‘To those who are annoyed that they can’t understand all the allusions, or who even admit that they have no idea of what I’m really getting at, I will merely reply that they should blame their own sterility and lack of education rather than my methods; they have wasted their time at college, bargain shopping for worn-out fragments of secondhand knowledge’.[36] The outright hostility towards modern society that these works contain thus shapes their very form and delivery.

With that in view, Debord’s use of détournement in The Society of the Spectacle can then be seen not as arbitrary, or ornamental, but rather as a mode of expression that accords with the book’s content. Détournement involves appropriating, altering and re-casting lines from other works, so as to breathe new, oppositional life into ideas whose meaning had become ossified (the most famous example can be found in Thesis #1, which re-works Marx’s own opening line in Capital). It accords with the book’s desire to animate the stifled vitality of spectacular society. Moreover, and despite the SI’s desire to avoid traditional aesthetics,[37] Debord’s attempt to unite form and content can also be viewed as possessing an aesthetic dimension. The Society of the Spectacle is not just a theoretical contribution to revolutionary struggle. It is that, certainly; but, to some degree, it also succeeds in instantiating its own demand that art and poetry should be united with revolutionary opposition and employed in active contestation. The cold elegance of the writing, and the latter’s poetic formulations and modernism, approach a kind of beauty that is one with the revolutionary politics that it endeavours to articulate: a beauty of negation, of change, destruction, and transformation, which operates within the very détournements from which the book is composed, and which forms part of its refusal to enter dialogue with, or condescend to, the culture that it attacks.

The theory of spectacle after 1968

In 1969, and in an essay titled ‘How Not to Understand Situationist Books’, in which they responded to reviews of Debord and Vaneigem’s books, the SI remarked that The Society of the Spectacle was ‘a book that lacked nothing but one or more revolutions’.[38] Two years after the book’s publication, and only one year after May 1968, they were also able to remark, with some satisfaction, that such unrest was ‘not long in coming’.[39]

As far as Debord and the SI were concerned, May 1968 provided at least partial confirmation of their claims. Yet, holding that the group had, by this time, made a major contribution, and recognising that its moment had passed, Debord terminated the SI in 1972. In his view, the group had served to articulate and further the struggles of its time, and if it remained in existence beyond such a period of relevance, it would risk becoming an obsolete spectacular figurehead.

Debord continued to write and produce films after the SI’s conclusion (including, in 1974, a cinematic version of The Society of the Spectacle), and he continued to employ the concept of spectacle in his work. In the years that followed 1968, he became increasingly focussed on the complicated patterns of revolt, repression, surveillance, manipulation and terrorism that arose in the aftermath of the uprisings. He became particularly fascinated by the Italian anni di piombo in this regard, and his study of these circumstances informed his other major work on the concept of spectacle: 1988’s Comments on the Society of the Spectacle.

Comments is, ostensibly, a much bleaker text than The Society of the Spectacle. The book holds that, in the years that followed 1968, the spectacle had ‘continued to gather strength’, and contends that it had ‘even learnt new defensive techniques, as powers under attack usually do’.[40] Comments thus sets out to detail the ‘practical consequences’ of ‘the spectacle’s rapid extension’[41] over the two decades that had passed since The Society of the Spectacle’s publication, and since May 1968. Comments lacks the traces of euphoria that inflect The Society of the Spectacle’s vision of impending revolution. It describes a social order that had proved capable of ‘eliminating’ almost ‘every organised revolutionary tendency’,[42] and it contends that ‘wherever the spectacle rules, the only organised forces are those that want the spectacle’.[43]

Comments is not, however, an admission of defeat[44] (Debord remarked in his correspondence, in connection to the Comments, that ‘the role of revolutionary critique is assuredly not to lead people to believe that the revolution has become impossible!’).[45] It is certainly less optimistic: its basic contention is that the conditions described in The Society of the Spectacle had deepened and become more entrenched, rendering revolution all the more important on the one hand, and yet all the more difficult to achieve on the other. Yet in 1992, two years before his death, Debord wrote a new preface to The Society of the Spectacle, in which he stated that his 1967 book still served to accurately describe the flawed nature of modern society, and in which he also made the following remark:

The same formidable question that has been haunting the world for two centuries is about to be posed again everywhere: How can the poor be made to work once their illusions have been shattered, and once force has been defeated?[46]

Nearly forty years later, that assertion may now seem rather hasty. Moreover, Debord’s commitment to total, uncompromising revolutionary change can be genuinely troubling; at times, it can seem to resemble a kind of furiously secular, but no less zealous, holy war. In consequence, ensuring that the concept of spectacle’s intimate ties to revolutionary politics are kept in view is surely essential to any critical evaluation of this work today. But, at the same time, there are aspects of Debord’s thought that can seem strikingly timely. Global politics has become marked by manipulation, confusion and conspiracy, the everyday has become subjected to new forms of material and existential impoverishment, and capitalist society’s evident inability to manage its own future is being forcibly demonstrated by the impending threats of global warming and by other environmental, economic and political crises. Within such a context, Debord’s assertion, and indeed the broader claims set out in this book, may then take on renewed and deepened significance.

References

Bunyard, Tom, 2018, Debord, Time and Spectacle: Hegelian Marxism and Situationist Theory, Chicago: Haymarket.

Bunyard, Tom, 2022, ‘Spectacle and Strategy: On the Development of Debord’s Theoretical Work from The Society of the Spectacle to Comments on the Society of the Spectacle’, in Selva: A Journal of the History of Art, 1:4, 2022.

Debord, Guy, 1989, ‘The Hamburg Theses of September 1961’, translated by Reuben Keehan, available at <http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/postsi/hamburg.html>.

Debord, Guy, 1998 [1988], Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, translated by Malcolm Imrie, London: Verso.

Debord, Guy, 2001 [1985], Considerations on the Assassination of Gerard Lebovici, translated by Robert Greene, Los Angeles: Tam Tam.

Debord, Guy, 2003a [1978], Complete Cinematic Works: Scripts, Stills and Documents, translated and edited by Ken Knabb, Edinburgh: AK Press.

Debord, Guy, 2003b, Correspondance Volume 3: Janvier 1965 – Décembre 1968, Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard.

Debord, Guy, 2004, Correspondance Volume 4: Janvier 1969 – Décembre 1972, Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard.

Debord, Guy, 2006, Oeuvres, Paris: Gallimard.

Lukács, Georg, 1971 [1923], History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics, translated by Rodney Livingstone, London: Merlin.

Marcus, Greil, 1989, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century, London: Faber and Faber.

Marx, Karl, 1975, Early Writings, translated by Rodney Livingstone and Gregor Benton, Middlesex: Penguin.

Situationist International, 1997, Internationale Situationniste, Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard.

Situationist International, 2006 [1981], Situationist International Anthology, translated and edited by Ken Knabb, Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets.

[1] Debord 2006, p. 1794.

[2] The reading that I set out here draws on Bunyard 2018. I that book, I present the book’s various intellectual, cultural and political sources in more detail, and attempt to reconstruct the peculiarly existential approach to Hegelian Marxism that underpins his work.

[3] Marx 1990, p. 772.

[4] Debord 2004, p. 140

[5] See, for example, his 1979 preface to the fourth Italian edition of The Society of the Spectacle, which includes the following remarks: ‘Of all those who have quoted from this book in order to acknowledge some importance in it, I have not seen one up till now who took the risk to say, even briefly, what it was about: in fact, it was their concern simply to give the impression that they were not unaware of it. … Most often the commentators pretended not to understand to what usage a book can be destined if it will never be able to be classified into any of the categories of the intellectual productions that the dominant society wants to take into consideration, and if it was not written from the point of view of any of the specialized trades that it encourages. Thus, the intentions of the author seemed obscure’ (Debord 2006, p. 1462-3).

[6] Debord 2004, pp. 455-6.

[7] SI 2006, p. 501

[8] ‘Situationism’, it should be noted, is a term that the SI hotly rejected: it suggests precisely the kind of fixed doctrine that the group opposed. ‘There is no such thing as situationism, which would mean a doctrine for interpreting existing conditions. The notion of situationism is obviously devised by antisituationists’ (SI 2006, p. 51; 1997, p. 13).

[9] SI 2006, p. 501.

[10] See, in particular, the SI’s text (authored by Debord) ‘The Beginning of an Era’, published in Internationale Situationniste 12.

[11] Debord 2006, p. 1461.

[12] Unitary urbanism was an attempt to combine architecture, urban planning, art and other creative means in the deliberate construction of forms of social interaction and lived experience.

[13] Psychogeography was a study of the effects that the geographical environment exerts on subjective experience and behaviour of individuals.

[14] The dérive, or ‘drift’, was a technique used in the study of psychogeography. Drifters would wander through the environments under examination, individually or groups, and note the responses and journeys that these environments prompted.

[15] Détournement was a technique in which existing cultural forms would be subverted and altered as to convey oppositional messages. The most famous examples are perhaps the SI’s altered comic strips, but one might think here of The Society of the Spectacle itself: many of its theses include passages from other texts that have been altered slightly (see, for example, Thesis #1, which modifies Marx’s opening line in Capital).

[16] SI 2006, p. 41; Debord 2006, p. 326.

[17] S.I. 2006, p. 40; Debord 2006, p. 325.

[18] Debord 2006, p. 195.

[19] SI 2006, p. 14; Debord 2006, p. 221.

[20] S.I. 2006, p. 40; Debord 2006, p. 325, translation altered.

[21] S.I. 2006, p. 40; Debord 2006, p. 325.

[22] Debord 2003a, pp. 18-9; 2006, p. 476; emphasis in the original.

[23] Debord 2003a, p. 32; 2006, p. 545.

[24] Debord 2003a, p. 31; 2006, p. 543.

[25] S.I. 2006, p. 141; 1997, p. 309.

[26] S.I. 2006, p. 141; 1997, p. 309.

[27] SI 2006, p. 93; 1997, p. 32.

[28] See Bunyard 2018, p. 29 for a list.

[29] Lukács 1971, p. 89.

[30] Marx 1975, p. 257.

[31] Debord 1989; SI 1997, p. 703, translation altered.

[32] Debord 2003b, p. 21.

[33] Debord 2006, p. 1463.

[34] Debord 2003a, p. 146; 2006, p. 1349.

[35] Debord 2003a, p. 35; 2006, p. 549.

[36] Debord 2003a, pp. 149-50; 2006, p. 1353.

[37] See, for example, Debord’s 1961 text ‘For a Revolutionary Judgement of Art’.

[38] SI 2006, p. 340; 1997, p. 615.

[39] SI 2006, p. 340; 1997, p. 615.

[40] Debord 1998, pp. 2-3, translation altered; 2006a, p. 1594.

[41] Debord 1998, p. 4; 2006a, p. 1595.

[42] Debord 1998, p. 80; 2006a, 1641.

[43] Debord 1998, p. 21; 2006a, p. 1605.

[44] See Bunyard 2022 for remarks on this point.

[45] Debord 2006, p. 450.

[46] Debord 2006, p. 1794.