Fred Orton has been a prominent figure in Marxist art history from the late 1970s onwards, writing mainly on modern European and American art and medieval sculpture and teaching on the highly influential MA in the Social History of Art at the University of Leeds.[1] His compelling, highly particular voice, helped transform a field of study and he will be hugely missed by his admirers and friends. Unlike many former allies, Orton never wavered from this intellectual-political commitment to Marx and Marxism. As with a number of other British art historians, his interest in the history and theory of art began while at art school. In his case, Coventry College of Art where Terry Atkinson, who taught there part time during his final year, and Michael Baldwin, a fellow student, went on to found the highly-influential collective Art & Language. Orton maintained a close interest in the British wing of Art & Language and, during the first part of the 1980s, this developed into collaboration when he became a member of the group, both writing and painting under their egis.

After graduation from Coventry College of Art in 1967, Orton did postgraduate work at the Courtauld Institute of Art, at the time a bastion of the establishment. But new approaches to art history were circulating. On leaving the Courtauld Institute, he taught for a while at Leicester Polytechnic (collaborations led to an opera Irma (1977) with composer Gavin Bryars and artist Tom Phillips, for which he wrote the libretto). In 1976, he was appointed at the University of Leeds by T.J. Clark. This was the period of the emergence of, what would now be recognised as, second-wave Marxist history of art, and the group at Leeds were a central node in the British formation. As with many others of the generation who pioneered the Marxist critique of art history, sometimes called the Social History of Art, Orton began working on nineteenth-century French art, in his case the Post-Impressionism of Van Gogh and others. Sometimes alone, but often writing with Griselda Pollock, Orton produced a series of pioneering studies that helped demystify the cult of Impressionism, insisting on the presence of class and capital in the making and reception of this art. Orton and Pollock were particularly committed to debunking the myth of Van Gogh as ‘primitive’ or mad genius and the investment of art history in such ideologically loaded categories, which occlude labour.

Important interventions followed, particularly the essay ‘Les Données Bretonnantes: la Prairie de Représentation’ (1980), again co-written with Pollock, on Paul Gauguin and Emile Bernard in Britany and the fantasy of an escape from modern social life, which is an ideology generated from within that life. However, Orton had taught art history in the art studio setting at Leicester Polytechnic before joining the Department in Leeds and Clark wanted him to teach a course for art students on postwar American art. Employing rhetorical analysis, he pursued a critique of modernist ideology on the surface of US abstract art. Marx, Wittgenstein, Derrida and De Man were all put to work. In the process, he developed his account of the dialectic between ‘surface matter’ and ‘subject matter’. He also switched attention from the critical explanations offered by Clement Greenberg, who had moved from Trotskyism to Cold War liberalism and formalism, to those of another one-time Trotskyist Harold Rosenberg. At the time, Greenberg’s work was undergoing something of a revival among British writers engaged with modern art, and Orton bucked this trend, insisting that Rosenberg offered a much more compelling and politicised version of Abstract Expressionism, which drew on Marx’s account of drama and the act in the Eighteenth Brumaire. Rosenberg’s essays of this period, including ‘Character Change and Drama’ (1932), ‘The Fall of Paris’ (1940), ‘Resurrected Romans’ (1948), ‘The Pathos of the Proletariat’ (1949), and ‘The American Action Painters’ (1952) are not only some of the most inventive and stimulating works of Trotskyist critical theory, but they are also a major contribution to the interpretation of Marx. For Rosenberg, the proletariat embodied a unique capacity for action, and if Cold War liberalism and Stalinist counterrevolution produced a hiatus in history, that potential was undimmed. Orton read the essay on action painting as a place holder for revolution, a practice that kept open possibility and an openness to the future during a period of political defeat.

Orton did not publish his influential lectures on the New York School. Instead, he turned to studying the painter Jaspar Johns, who, in the wake of Abstract Expressionism, reintroduced imagery into painting without abandoning the ambitious project of modernist art. Drawing on Wittgenstein and Duchamp, Johns created a number of important pictorial conundrums. Orton’s first study of Johns, co-authored with Charles Harrison, can be seen as emerging from concerns in Art & Language. While the issues raised in that essay never disappeared, his subsequent work, culminating in Figuring Jaspar Johns (1994) drew on theories of allegory and rhetorical analysis, particularly the tropes of metonymy and synecdoche. His key sources for this analysis were Benjamin’s Origin of German Tragic Drama, the essays of Paul de Man, and the thought of Marx & Engels. He argued that, while high modernism worked within the dominant aesthetic framework of the Symbol (and, in modernism, the allied idea of metaphor), Johns was an allegorist, who cut against the idea of organic unity and immediacy central to aesthetic ideology and its key ideas of ‘origin’, ‘intention’ and ‘expression’. He describes explanations of this kind as ‘the dominant theory of modern art’ and he usually cites Greenberg for his examples. It is the role of curators, art historians and critics – ‘cultural managers’ as Orton called them – to stabilise such claims and, for him, it was the task of the Marxists in these areas to undermine this ideology.

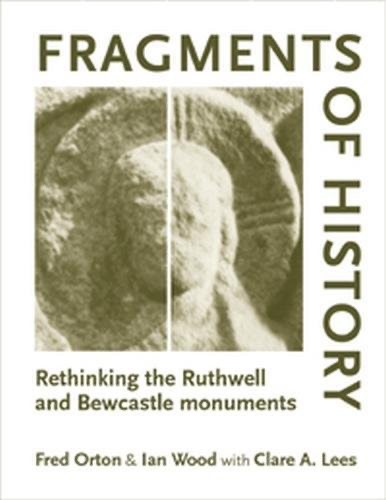

In the late 1990s, Orton again shifted focus and began writing about two important Anglo-Saxon monuments: the so-called Ruthwell Cross and the Bewcastle Cross. There are precedents for this switch. The great American Marxist art critic, Meyer Schapiro, wrote studies of medieval sculpture, including a ground-breaking study of the Ruthwell Cross, as well as being the first art historian to teach modern art in a university department (Columbia). The German Marxist O.K. Werckmeister has also written important studies of modern art and culture as well as analyses of medieval art, including a still fecund study of ideology in the Bayeux tapestry. The book that Orton co-wrote with Clare A Lees and Ian Wood – Fragments of History: Rethinking the Ruthwell and Bewcastle Monuments (2007) – provides not only a brilliant analysis of medieval stone monuments, but, as Andrew Hemingway noted of the book, a fascinating reminder that these monuments are themselves ‘documents of power and conflict’ part of a ‘complex history of conquest and struggle’.

Orton set enormous store by close reading (and close looking). The resource for this work is the tradition of literary criticism from New Criticism to de Man, alongside Marxist ideology critique. Orton was an entertaining and impressive lecturer, but his most influential teaching has taken the form of intensive seminars involving detailed study of texts. This work involved reading sentence by sentence, line by line, paying attention to figures and tropes. He carried over this practice of close reading/looking into his published writing. This model of close reading, is also a form of slow reading, giving the text or artwork its due and trying to get the presentation right, rather than rushing to judgement. There are few historians of art who have ever been able to match his sustained attention. Orton looked at paintings until they seemed to beg for mercy. The results of this kind of study are evident in his extraordinary examinations of artworks ranging from Cézanne to Johns.

At least since the early 1990s, Orton studied Paul de Man alongside Marx, running seminars on both. Terry Eagleton presented probably the best-known Marxist critique of de Man in his essay ‘Capitalism, Modernism and Postmodernism’, arguing that de Man’s work was quietist, depicting any political practice as necessarily self-blinding (and self-defeating). For Eagleton, there was a ‘steady, silent anti-Marxist polemic’ running throughout de Man’s essays. However, Orton was not alone in gravitating towards de Man’s critical unravelling of the quick meaning fix. For example, critic John Roberts once described de Man as ‘the “favourite” deconstructionist for historical materialism’. Marxist critics as different as Fredric Jameson, Michael Sprinker, T.J. Clark and Gail Day (an Orton student), to name just a few, have all been drawn to de Man’s work. Orton’s position was never a straightforward deconstructionism or postmodernism, not even anti-realism. Marx, Wittgenstein and Richard Wollheim were always too present in his thinking for that. For Orton, these thinkers are guides to reading politically or ethically. What he found in his practice of close, rhetorical reading is a model for ideology critique, which undercuts false reconciliation in a society of social division. De Man coined the term ‘aesthetic ideology’ to describe that species of interpretation that finds meaning to be immediately accessible and untroubling. His central point is that close attention to the text demonstrates that such claims cannot be sustained.

In modernist theory, whether aestheticist or formalist, the absolute autonomy and self-identity of art appears as the figure for supposed cohesion, separating the artwork from history or society. A related ideology consists of treating authors or artists as autonomous selves, ontologically prior to the artwork. Breaking open the unity of the artwork, refusing the autonomous author and not allowing meaning to settle, Marxist thinkers have found fragmentation, negativity and temporality more amenable critical concepts with which to conduct critical work. Closure and fixity are enemies of dialectical thought and in their rejection, Marxists might find many points of agreement with Paul de Man. For Orton, this was always allied to Marx’s critique of ideological conjuring tricks, where false or bad totalities like the term ‘population’, make social class disappear from view. Here self-deception or the ‘false consciousness’ of The German Ideology is akin to misreading.[2] ‘What is The German Ideology’, Orton writes, ‘if not an extended polemic against formalism, false historicism and Utopianism?’ All are false reconciliations, in a hurry to arrive at the absolute. In his book for the Historical Materialism series, he suggests: such an approach makes the ‘unbearable bearable, the thinkable more or less unthinkable, the aberrant normal’.

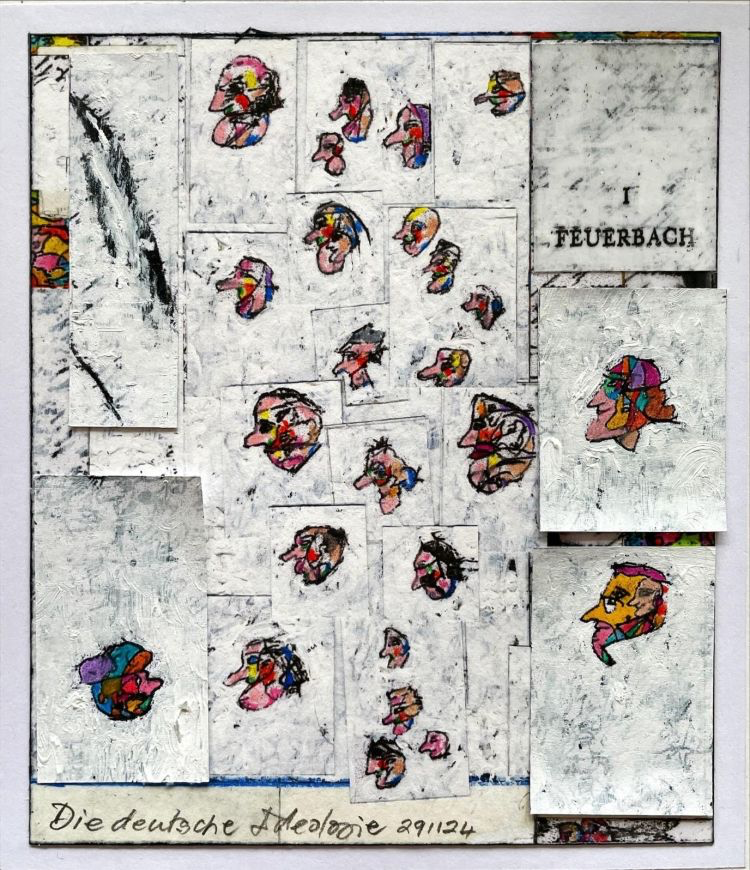

After his retirement from teaching at Leeds, Orton returned to making artworks, producing hundreds of drawings based on a page from The German Ideology, probably by Engels, which contained caricatures of the Young Hegelians. He reworked the page with paint and pencil on Gliese print and his disparaging reference to this work as his ‘colouring book’ is clearly a smokescreen for an ambitious painting practice. There is currently an exhibition of some of these works at the University of Leeds: https://ahc.leeds.ac.uk/leeds-global-history/events/event/3391/fred-orton-the-german-ideology-plates-from-a-marx-engels-colouring-book

Fred is survived by his partner Miranda Orton and their daughters Daisy and Emmylou.

Fred Orton, Untitled.

Publications by Fred Orton

I Books

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, Vincent van Gogh: Artist of his Time, Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1978

Charles Harrison and Fred Orton, A Provisional History of Art and Language, Paris: Editions Fabre, 1982.

Charles Harrison and Fred Orton eds., Modernism, Criticism, Realism: Alternative Contexts for Art, London: Harper & Row, 1984.

Thom Mayne and Fred Orton, Morphosis: Tangents and Outtakes, London: Artemis, 1993.

Fred Orton, Figuring Jasper Johns, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Fred Orton, Jasper Johns: The Sculptures, Leeds: The Henry Moore Institute, 1996.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, Avant-Gardes & Partisans Reviewed, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996.

Catherine Karkov and Fred Orton eds., Theorising Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2003.

Fred Orton & Ian Wood with Clare Lees, Fragments of History: Rethinking the Ruthwell and Bewcastle Monuments, Manchester University Press, 2007

II Book chapters, journal essays and catalogue essays

Fred Orton, ‘Vincent van Gogh in Paris 1886-1888’, Bulletin of the Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh, Vol. 1, No. 3, Autumn 1971: 2-12.

Gavin Bryars and Fred Orton, ‘Morton Feldman’, Studio International, Vol. 192, No. 984, Nov-Dec. 1976: 244-248.

Republished as: Gavin Bryars and Fred Orton, ‘Studio International Interview, Fred Orton and Gavin Bryars, 27 May 1976’ in Morton Feldman Says: Selected Interviews and Lectures 1964-1987, edited by Chris Villars, London, Hyphen New Series, Hyphen Press, 2005: 63-73.

Gavin Bryars and Fred Orton, ‘Tom Phillips’, Studio International, Vol. 192, No. 984, Nov-Dec. 1976: 290-296.

Fred Orton, ‘Vincent van Gogh and Japanese Prints: An Introductory Essay’ in Japanese Prints Collected by Vincent van Gogh, edited by L. Couvée, pp. 14-23, Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh, 1978.

Fred Orton, ‘A Little Art History’, Open Letter: A Canadian quarterly review of writing and sources, ser. IV, No. 1-2, Spring 1978: 158-180.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Les Données Bretonnantes: la Prairie de Représentation’, Art History, Vol. 4, No. 3, Sept. 1980: 314-344. Republished in Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology, edited by F. Frascina and Charles Harrison, London: Harper & Row, 1983: 285-304.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed’, Art History, Vol. 4, No. 3, Sept. 1981: 305-327. Republished in Pollock and After: The Critical Debate, edited by F. Frascina, pp. 167-183, London: Harper & Row, 1985 and Pollock and After: The Critical Debate Second Edition, edited by Francis Frascina, London: Routledge, 2000: 211-226.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Cloisonism?’, Art History, Vol. 5, No.3, Sept. 1982: 341-348.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Jackson Pollock, Painting and the Myth of Photography’, Art History, Vol. 6, No. 1, March 1983: 114-122.

Michael Baldwin, Charles Harrison, Fred Orton, M. Ramsden (as Art & Language), ‘A Cultural Drama: The Artists Studio’, Art and Language (exhibition catalogue), Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, Sept-Oct. 1983: 3-25.

Charles Harrison and Fred Orton, ‘Jasper Johns: Meaning What You See’, Art History, Vol. 6, No. 1, March 1984: 78-101.

Fred Orton, ‘Art & Language’, The Fifth Biennale of Sydney. Private Symbol: Social Metaphor (exhibition catalogue), April-June 1984: n.p.

Fred Orton, ‘Reactions to Renoir Keep Changing’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1985: 28-35.

Fred Orton, ‘Modernism, Postmodernism, and Art Education (English)’, Circa, No. 28, May-June, 1986: 62-64.

Fred Orton, ‘Present, the Scene of … Selves, the Occasion of … Ruses’, Block 13, Winter, 1987: 5-19. Republished in Ruses’ in Foirades/Fizzles: Echo and Allusion in the Art of Jasper Johns, edited by James Cuno, pp. 167-192, Los Angeles: Wight Art Gallery, U.C.L.A. 1987, and Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. Also in The Block Reader in Visual Culture, edited by the Block editorial board, London: Routledge, 1996: 87-114.

J. R. R. Christie and Fred Orton, ‘Writing on a Text of the Life’, Art History, Vol.11, No. 4, Dec. 1988: 545-564.

Fred Orton, ‘On Being Bent Blue (Second State): An Introduction to Jacques Derrida/A Footnote on Jasper Johns’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1, 1989: 35-46.

Fred Orton, ‘Action, Revolution and Painting’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 14, No. 2, 1991: 3-17.

Republished in American Abstract Expressionism, edited by David Thistlewood, pp. 147-178, Liverpool: Tate Gallery and Liverpool University Press, 1993. Also anthologized in anthologized in Pollock and After: The Critical Debate Second Edition, edited by Francis Frascina, London: Routledge, 2000: 211-226.

Fred Orton, ‘J. Johns’s Flag: A Different Kind of Beginning’, Over Here: Reviews in American Studies, Vol. 11, No. 2, Winter 1991: 64-84.

Fred Orton, ‘Footnote One: The Idea of the Cold War’ in American Abstract Expressionism, edited by David Thistlewood, Liverpool: Tate Gallery and Liverpool University Press, 1993: 179-192.

In German as ‘Footnote Eines: Die Idee das Kalten Krieg’ in Abstrakte Expressionismus, Konstruktion eines Aesthetik, edited by R. Breugel, Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 2000.

Fred Orton, ‘Figuring Jasper’s Flag (First Draft): A Different Kind of Beginning’ in Kunstlerischer Autausch/Artistic Exchange, Akten des XXVIII Internationalen Kongresses für Kunstgeschichte, Berlin, 15-20 Juli 1992, edited by Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1994: 703-711.

Fred Orton, ‘Figuring Jasper Johns’ in Art Has No History! The Making and Unmaking of Modern Art, edited by John Roberts, London: Verso, 1994: 111-132.

Fred Orton, ‘(Painting) Out of Time’, Parallax: A journal of metadiscursive theory and cultural practices 3, September 1996: 99-112,.

Fred Orton, ‘The Object After Theory (Figuring Jasper Johns – Supplement 1: Flag)’, de-, dis-, ex, Vol. 1, Ex-cavating Modernism, 1996: 23-34.

Fred Orton, ‘Rethinking the Ruthwell Monument: Fragments and critique; tradition and history; tongues and sockets’, Art History, Vol. 21, No. 1, March 1998: 65-106.

Fred Orton, ‘Northumbrian Sculpture (the Ruthwell and Bewcastle Monuments): Questions of Difference’ in Northumbria’s Golden Age, edited by Jane Hawkes and Susan Mills, Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd., 1999: 216-227.

Fred Orton, ‘Beginning with Intention’ in The Dynamics of Now: Issues in Art and Education, edited by William Furlong, Polly Gould and Paul Hetherington, London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 2000: 137-149.

Fred Orton, ‘On the Intention of Modern(ist) Art’ in A Companion to Art Theory, edited by Paul Smith and Carolyn Wilde, Oxford: Blackwell, 2002: 229-243.

Lisa Joyce and Fred Orton, ‘“Always Elsewhere”: An Introduction to the Art of Jeff Wall (A Ventriolquist at a Birthday Party in October, 1948)’ in Jeff Wall: Photographs, Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2003: 8-33.

Fred Orton, ‘Rethinking the Ruthwell and Bewcastle Monuments: Some strictures on similarity; some questions of history’ in Theorising Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, eds. Catherine Karkov and Fred Orton, West Virginia University Press, 2003: 65-92.

Fred Orton, ‘Northumbrian Identity in the Eighth Century: Style, classification, class, and the form of ideology’, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Winter, 2004: 95-145.

Fred Orton, ‘At the Bewcastle Monument, In Place’ in The making of Place, Medieval to Modern, edited by Clare A. Lees and Gillian R. Overing, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006: 29-66.

Fred Orton, ‘SUSPENSA VIX VIA FIT: Jasper Johns’ catenary, the everyday self, the work of art/aesthetic self, and the art object’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2004: 79-93.

Republished in Value: Art: Politics. Criticism, Meaning and Interpretation after Postmodernism, edited by Jonathan Harris, Liverpool University Press, 2007.

III Television and Radio Programmes for the Open University

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Rooted in the Earth. Vincent van Gogh: The Potato Eaters’, Open University/B.B.C. T.V., A315 Modern Art & Modernism (25 mins.), 1982.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘The Museum of Modern Art’, Open University/B.B.C. T.V., A315 Modern Art & Modernism (25 mins.), 1983.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Peasants and Paintings of Peasants’, Open University/B.B.C. Radio, A315 Modern Art & Modernism (25 mins.), 1983.

Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, ‘Art and U. S. Imperialism’, Open University/B.B.C. Radio, A315 Modern Art & Modernism (25 mins.), 1983

Fred Orton, ‘Jasper Johns’s Flag’, Open University/B.B.C. T.V., A316 Modern Art – practices and debates (25 mins.), 1993.

Fred Orton, ‘Jasper Johns’, Open University Video, A318 Art of the Twentieth Century, video, (30 mins.), 2003.

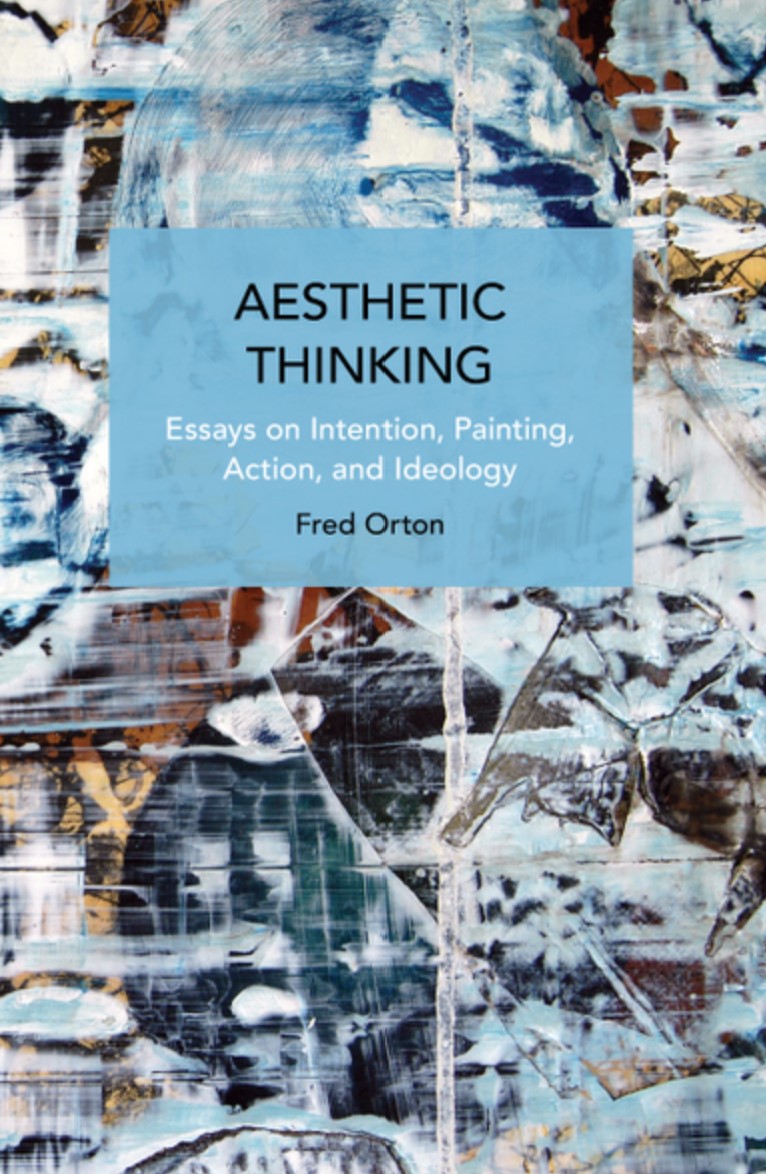

[1] This is a shortened and adapted version of the introduction to Orton’s book Aesthetic Thinking: Essays on Intention, Painting, Action and Ideology in the Historical Materialism Book Series, Brill 2021/Haymarket 2022.

[2] Though, Orton always notes that Engels does not speak of ‘false consciousness’, but, rather, sees ideology as ‘a process accomplished by the so called thinker consciously … but with a false consciousness’.