A French version of this interview was originally published at http://revueperiode.net/des-salaires-pour-facebooker-du-feminisme-a-la-cyber-exploitation-entretien-avec-kylie-jarrett/

- You recently published Feminism, labour and digital media : the digital housewife[1], in which you tried to frame the booming empirical research about digital technologies on the ground of post-operaist marxism and digital labour theories on the one hand, and of feminism on the other. What is decisive in the contribution of the first two ? Why should we put political economy, and even more specifically the concept of labour, at the core of our understanding of digital mediations?

Political economy needs to be central to our understanding of digital mediations in order to de-naturalise the particular conditions associated with the contemporary internet and the Web more specifically. When I tell my undergraduate students that researchers and users used to have debates about whether or not the internet should be commercialised, they are mostly just puzzled (and a little amused). For them, there is no other reality than the proprietary walled gardens that is their digitally mediated experience today. Unpacking the nature of this commercialisation activity, offering it up to critique and conceptualising how it could be other is thus vital to the work I do as an educator but also as an internet researcher.

In my research, the work of autonomist Marxism and the ways in which people like Tiziana Terranova[2] used it to interpret the digital media economy gave me a useful language to describe the kinds of exchange relationships I’d been seeing since I began researching the work of online X-Files fans in my undergraduate dissertation. The social interactions on these fan sites could be read as forms of user resistance to the ideological imperatives of the TV programme and commodification of culture, but I was more interested in how, despite this, they also created value for the commercial entities associated with the production. To be able to conceptualise digital users’ activity as a form of surplus value-generating labour was useful for understanding this phenomenon. This has only become more important as the unquenchable thirst for content by social media platforms demands more and more user-generated inputs and as digital networks embed themselves deeper into the cultural and social fabric.

More broadly, though, autonomist thinking is extremely useful in explaining the nature of late 20th and early 21st century capitalism after neoliberal governance, economics and politics settled in very comfortably as the global hegemon and work re-shaped by technological and cultural change. The idea of the social factory (although I have some trouble with its application) is important for understanding a context where valorised forms of work centre on the cognitive, the communicative and the affective, saturating subjectivity with the potential for capitalist expropriation. This changes the critical battleground against capital from inside formally defined factory gates to sites of leisure, self-making and interpersonal relationships so that ideas relating to the relative autonomy of workers such as those espoused in Operaismo thinking gain new salience and political utility.

- The ground-breaking works of operaist authors like Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James, Leopoldina Fortunati or Silvia Federici[3] remained largely ignored and marginalized in operaism. How did it end up undermining the immaterial/digital labour claims?

There is a particular blind spot in dominant modes of research for the work of women, queer scholars and people of colour which leads to limitations in how we understand the critical terrain. When it comes to digital labour, this is not just an effect of the difficult history of the intersection of Marxism and feminism, but of internet research more generally where the theoretical wheel has consistently been re-invented. The marginalisation of feminist thinkers and thinking about conditions of domestic labour specifically lead to unsubstantiated claims of the novelty of contemporary conditions of precarity and in which life and work become indistinguishable; my concern with the mobilisation of the idea of the social factory. This, in turn, meant that existing and valuable models and critiques of such labour practices – materialist understanding of domestic work, for instance – were overlooked in favour of re-invented versions of critique.

Noting but leaving aside the symbolic violence done to feminist scholars and activists, this elision also meant a reduced critical spectrum from which to interpret and to act, which is damaging for anti-capitalist politics. Failure to recognise the conditions in which people who aren’t white, cis, het, men have always worked has meant no capacity to learn from, to use Rema Hammami’s[4] ideas, subaltern survival and its suite of tactical and structural subversions. Centralising these perspectives is thus important, not only because they provide relevant and useful frameworks for understanding contemporary labour conditions, but because they have much to contribute to struggle.

- The discussion of the boundaries between labour and leisure, production and consumption, productive and improductive, or alienated and free labour, has been revived recently precisely because with digital networks, capital has been given the opportunity to freely benefit from users’ spontaneous playful activity. So would you say that our online activity is productive yet free, and in what sense? Or did such networks just make all these boundaries collapse?

I would not suggest that digital networks made such boundaries collapse because the critical history of domestic work and the formation of subjectivity within the gendered, sexed and raced division of labour tells us those boundaries were always illusory. For women and people of colour, there has never been a space that was not fundamentally shaped by the ways in which capitalism embedded patriarchal and racist logics. Even individual subjectivity is fundamentally articulated in relation to these power relations so that distinctions between labour and leisure do not hold when viewed from feminist or queer critical perspectives.

What digital networked technology has done, though, is make that collapse more visible, and certainly more normative. In a throwaway line in the book I say that it feels as if the exploitation of immaterial labour was only “invented” when it moved out of the kitchen and onto the internet – when it started happening to white, middle class, cis-, hetero, able men. Of course, these men are also fundamentally shaped as subjects by the capitalist mode of accumulation, particularly as masculinity and whiteness are so fundamentally bound to work, but the privileged position of white masculinity in capitalism means it was possible to still view selfhood as outside of capital. The pervasion of digital networks overtly demanding the collapse of distinctions between labour and leisure means that this subjectification has become harder to ignore.

That said, there is something new about the mechanisms of capture associated with digital networks. Digitisation works intensively and extensively to abstract the inalienable – to make it quantifiable and measurable – in ways that shapes the form of expropriation. We can think here about how quantification technologies like self-trackers work to assess mood through heart rate, for instance, providing a particular set of measures of subjectivity which then enters into self-management or, indeed, workplace management as seen in the work of Phoebe Moore[5].

It is important to recognise, though, that this doesn’t mean digital technologies actually capture mood, subjectivity or affect. They can only ever capture a reduced version of those inalienable dimensions of self, drawing inferences from externalisations of inherently internal processes. While capitalism doesn’t care that it “really” understands you, for it will mobilise its assumed version of you regardless of its veracity, it isn’t entirely able to capture what makes us “us”. This is where the relative autonomy of workers relates again to digital networks. Our digitally mediated activity remains free for it is producing elusive affects, richly meaningful activities and non-market relationships and exchanges, even while it is embedded within a capitalist logic. This is also a feature of domestic work’s relationship to capital which is another reason it serves as a useful model for thinking about this work.

- Who is the « digital housewife »? And what makes her or him specifically « digital »? Social reproduction theories demonstrated how the self-valorisation of capital rests heavily on a second circuit consisting in the reproduction of the labor power itself, which demands huge amounts of labour : material domestic chores, care for children and elders, emotional support and affection, etc. How does it involve digital technologies in particular? What is the relation of the « digital » housework to the rest of the reproductive work? Is the former different somehow?

It would be absurd, and probably offensive, to conflate the messy, physical, often degrading dimensions of material domestic and care work to the kinds of fiddling with social media platforms I focus on in my book. In particular, using a social media platform lacks the structural and sometimes violent coercion associated with unpaid domestic labour. These are fundamentally different activities in terms of importance, both economically and socially.

The digital housewife, then, is not in direct correspondence with the material activity of domestic work but is used as an analogy to indicate how the kinds of work undertaken by digital media users has the same structural relationship to capitalism as domestic work – fundamental to surplus value-creation but also capable of generating non-market, inalienable products. This hybridity and multiplicity is a feature of all kinds of reproductive activity. As Silvia Federici reminds us in Revolution at Point Zero[6], reproductive work is always in tension because how we produce and reproduce embodied consciousness in capitalism is both in the market and without, always threatening to spill over in excess. That is its transformative potential and hopefully the wider point that can be drawn from my study of a narrowly defined set of relatively frivolous activities such as using social media platforms.

- Digitally mediated social interactions would then be an instanciation of these « hybrid » activities, as you name them, meaningful and free, yet at the same time exploited, as is domestic labour. But the latter, potentially meaningful indeed, also appears as a toilsome time-consuming activity that one, having enough resources, could reasonably want to delegate to nannies, caterers, laundry services, profesionnal cleaners and other paid domestic workers. Moreover, the recognition of these activities as actual work has been the object of political struggles. Do you think that digital relations are somehow lived and contested as labour relations as well ?

Contestation is inherent to all reproductive work, including the work of consumption – Cultural Studies taught us this a very long time ago. In digital networks, we can see this in the disconnection strategies described by Ben Light[7] that allow users ostensibly to manage conditions of context collapse in social media but which, in effect, work as the withdrawal of labour. People also regularly use ad blockers, anonymising routers or game the data capture systems of the corporate Web by inserting false information, all of which work to sabotage the seamless exploitation of their online activity. Whether these acts are conceptualised as a struggle in labour relations is a different question and not one I can answer. Active recognition, though, may not be necessary for these acts to be effective in reducing user exploitation.

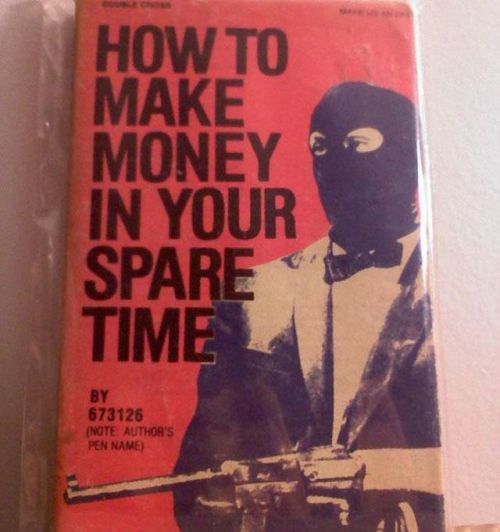

The Wages for Facebook[8] campaign is another mode for articulating struggle and one overtly linked to labour relations. Obviously drawing on the animating principle of the feminist Wages for Housework campaigns of the 1970s, its manifesto is less about seeking compensation for labour conducted for Facebook as its name would suggest, but about demystifying the centrality of capitalist corporations within the social fabric and seeking the agency that comes from formally contracted labour. I am not sure it has wide subscription but indicates the growing awareness of the capitalist expropriation of user data and specifically in terms of labour relations.

But when we talk about contestation, it is quite important to clarify what kinds of digital interactions we are discussing. The idea of digital labour, or labour which is mediated by digital platforms, extends from the exploitation of the labour of producing a tweet by a comfortable, middle-class professional to the battle of Uber drivers or TaskRabbit workers to earn a basic income. Struggle and the stakes of that struggle are thus of different scales of importance and have more or less clear links to labour relations. I am currently more interested in the forms of struggle associated with the latter, more materially exploited labour activities and there is some fascinating political activity taking place in this arena. The recent legal recognition of Uber drivers as employees in a couple of jurisdictions has been an important victory for workers, but we can also look at Julie Yujie Chen’s[9] work on Chinese drivers for different forms of struggle related to tactical subversions of the technology and mechanisms for organisation. So, I would argue that there is ample evidence of digital relations being centralised in lived labour politics.

- What could be the potential practical outcomes – in terms of political struggles – of the reading of digital networks through the conceptual figure of the digital housewife?

This is something I am still working through. I wrote my book mostly out of frustration at the marginalisation of feminist thought in discussions of user labour and it is really very narrowly targeted. Since its publication, though, I have been gratified to see the range of political discussions into which people have placed it, but this has also involved some reflection on the wider implications of the digital housewife or, more accurately, the centralisation of social reproduction.

One valuable line of thought that emerges from exploring reproductive work as work is consideration of longer value chains in our critique of capital. Often the seat of struggle or the focus of economic critique is a singular point in a value chain, usually that involving the production of a commodity. Wage equality is one of these struggles. This leaves various other sites for intervention into the capitalist infrastructure, such as self-making in domestic contexts, outside of the critical framework for how we change or overturn capitalism. This is not to dismiss the importance of struggle against capitalism by workers in formal institutional contexts, but demands we additionally look to changing the reproduction of that exploitative framework. If, as Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams[10] contend, we need a counter-hegemonic project to challenge platform economics, then it becomes essential to draw into our view those sites we don’t typically recognise as labour, but in which economic logics are normalised and materialised. These are the sites of social reproduction which, to return to Federici, is ground zero for political action.

As argued by many contributors to the excellent Social Reproduction Theory collection edited by Tithi Bhattacharya[11], paying appropriate due to social reproduction also intervenes in the technical and political composition of class, allowing for solidarity to be generated on grounds other than structural relationships to waged work. The inclusion of what might be termed (or disparaged as) “identity politics” into class struggle – recognising the oppressions of gender, race, sexuality, ability, sex as part of the totality of capitalism but with their own histories, trajectories and resistances – allows for the generation of new alliances and collective action addressing sites in which contemporary capitalism exploits markers of difference and associated power differentials. These points of solidarity may not be singular or fixed, for these other dimensions of economic subjection overlap, extend past or undermine long-standing assumptions about the textures of capitalist exploitation in ways that multiply political points of contact. Nevertheless, their articulation, and the ongoing negotiation of those articulations as the political landscape shifts, will facilitate struggle that doesn’t merely replicate the various oppressions entrenched by capitalism. That should be the goal of any form of resistance and so consideration of reproductive spheres needs to be centralised.

[1]Jarrett Kylie,Feminism, labour and digital media: the digital housewife, New-York, Routledge, 2016.

[2]Terranova Tiziana, “Free labor: producing culture for the digital economy.”Social Text 18 (2): 33-58, 2000.

[3]Dalla Costa Mariarosa & SelmaJames (ed.),The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, Bristol, Falling Wall Press, 1972;Fortunati Leopoldina,The Arcane of Reproduction: Housework, Prostitution, Labour and Capital, Hilary Creek (trad.), Autonomedia, New-York, 1995;Federici Silvia,Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn (NY), Autonomedia, 2004.

[4]Hammami Rema, “Precarious Politics: The Activism of “Bodies That Count” (Aligning with Those That Don’t) in Palestine’s Colonial Frontier”, in Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay (dir.),Vulnerability in Resistance, pp. 167-190, Durham, Duke University Press, 2016.

[5]Moore Phoebe V.,The quantified self in precarity: work, technology and what counts, Abingdon, Oxon, Routledge, 2018.

[6]Federici Silvia,Revolution at point zero: housework, reproduction and feminist struggle, PM Press, Oakland, California, 2012.

[7]Light Ben,Disconnecting with social networking sites, Basingstoke (Hampshire), Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

[8]http://wagesforfacebook.com/

[9]Chen Julie Yujie, « Thrown under the bus and outrunning it! The logic of Didi and taxi drivers’ labour and activism in the on-demand economy »,New Media & Society, Online First, 2017.

[10]Srnicek Nick and Alex Williams,Inventing the future: postcapitalism and a world without work (2nde éd.), London, Verso, 2016.

[11]Bhattacharya Tithi (éd.),Social reproduction theory remapping class, recentring oppression, London, Pluto Press, 2017.