HM at 20 and 16

For the journal’s 20th anniversary, we repost here extracts of interviews with Esther Leslie for HM in 2017 and with Peter Thomas for Jacobin in 2004, both conducted by George Souvlis.

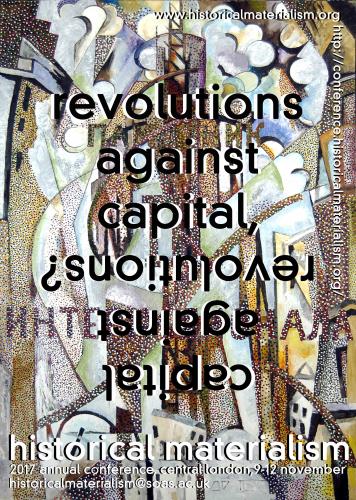

HM London 2017: Revolutions Against Capital, Capital Against Revolutions?

9-12 November at the SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) Main building, Russell Square (more details below).

*** ONLINE REGISTRATION IS NOW CLOSED. PLEASE REGISTER AT THE DOOR ***

*** DRAFT PROGRAMME NOW ONLINE ***

*** ABSTRACTS AVAILABLE HERE ***

*** FULL INTERVIEW WITH EDITOR ESTHER LESLIE ***

EXTRACTS OF NEW INTERVIEW WITH ESTHER LESLIE BY GEORGE SOUVLIS – HM AT 20 – 6 NOVEMBER 2017

GS: Now let’s discuss a bit the Historical Materialism initiative, now in its twentieth year, in which you are one of the founding members. Let’s begin with how the publication of the journal of Historical Materialism began. What were the initial aspirations for it? Could you mention some continuities and discontinuities in the twenty years history of the journal?

EL: I was not there right at the beginning. I was brought in before the first issue appeared though, so while not a founder, I have been involved since the journal has been in existence. We were initially self-published, did it all ourselves, including putting the journal in envelopes in my living room. The partnership with Brill has changed that and imposed on us a certain regularity, mechanized processes, and it has professionalized certain aspects – paying a copy editor, for example. We inhabit also a different environment of scholarly journals and online publishing nowadays. But I don’t think those changes have fundamentally altered the way in which we come together as a group of editors and discuss each article sent to us, commission reviews, argue over the direction of the journal, the necessity or not of a certain piece. I believe we wanted a journal which could represent the variety of ways in which Marxism could be brought to bear on aspects of the world. We did not want to be stuck in disciplinary silos but thought that one of the more brilliant things about Marxism is how it refuses those divisions, or if it does not refuse them, it becomes stupid. I am not claiming that we do not publish Fachidioten in the journal, of course, but the aspiration at the start was to publish articles that emerged from a Marxist perspective and could be read by anyone who was engaged in that mode of thinking – or interested to learn more about it – and acting, irrespective of theme. We wanted to represent the work of both the established scholars in Marxism and a younger or newer generation. We had aspirations to be the leading Marxist journal. We have tried to be supra-sectarian – and have weathered some difficult moments as groups on the Left around us have collapsed, gone rotten, recomposed, been riven apart. The board has constantly replenished itself, which has been a good thing, bringing in international perspectives, which enabled us to not get too embroiled in the catastrophic moves of parts of the UK Left. Perhaps it means that there is little collective memory of what we have been – but that is not a bad thing. Why look back, to glorious or inglorious pasts? One continuity has been the provision of covers by Noel Douglas. 20 years of covers is an achievement – but then these covers are also a tracking of the political events, highs and lows, in the world and so form in themselves a museum of world struggles, wins and defeats.

GS: Another significant aspect of the Historical Materialism project is the conferences that it organises and which have a global character, considering that they are now held annually in four continents (India, Europe, Australia, USA/Canada). Would you like to comment on the origins of this and its transformation through time?

EL: The conference began in 2004. It was much smaller, of course. It was even more chaotic than it is nowadays – we have learnt much about event planning and have been lucky to have been aided by some formidable organisers – always women. The conference grew in the subsequent years and is perhaps stable in terms of numbers now, but we always hope for expansion, for more people than we could possibly cope with, because for us, unlike other conferences, our conference is some sort of gauge of the significance, resonance, importance of our mode of comprehension, of Marxism in the world. We like to think that the conference is a must-do event for the global Left and enjoy the buzz of people meeting and re-meeting, quite apart from the papers that are delivered. It is not easy to organize and we do not really have institutional support, so it is in many ways done from the bottom up, which is why people should give us some slack if things do not run perfectly. The conference is franchised, so to speak now, with satellite events happening in other countries. I hope that means that the space for committed, intelligent Marxist work has expanded in the world and perhaps we have contributed to that. We have also learnt from that expansion, and from the drawing in of international voices. We are conscious that there is much beyond the Western tradition and also we have turned more attention to questions of sexuality and gender in later years.

GS: The conferences have succeeded at creating a new solid radical milieu around them. What else has HM accomplished?

EL: There is the book series, which has felled quite a few forests, and also, hopefully, circulated and recirculated some important materials. Some of the books in the series have been honoured with the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher prize, as recognition of their import. HM has kept Marxism as a point of attraction through years in which the Left has been, as ever, under assault, including from within its own ranks. To be able to meet together, hear each other, discuss, make future plans, develop projects, is positive.

Maia Pal: Not everyone on the radical left is a fan of anniversaries, perhaps considering their often stale and fixed look back into the past. This year’s HM conference set out to celebrate a few – the centenary of the Russian Revolution, the publication of Marx’s Capital, the journal’s birth… What do you think this says about the HM project, the left in general and the topic of memory your work generally explores? Finally, could you say something about your paper for this year’s London conference, ‘Lenin and the body in memorialis and the ecstatic sexuality in Eisenstein’s film’ which perhaps explores this desire to keep the revolutionary past alive?

EL: The celebration of anniversaries is usually reactionary. As I said earlier, why look back on glorious or inglorious pasts? Of course, I also take from Benjamin the idea that we have to hold onto the tradition of the oppressed, have to keep the red thread, the weak messianic force of resistance going, because otherwise the only story, or history, that remains is that of the victors. Much celebration is celebration by the victors. The monument to Benjamin in Port Bou, where he committed suicide, is to some extent sensitive to this. The memorial by Dani Karavan is in the idiom of the post-conceptual memorial as artwork. A narrow shaft leads one down to the perilous sea, in order to make us think about loss, danger, death. Etched on the glass of the memorial is, in several languages, a phrase from Benjamin, which observes: ‘It is more arduous to honour the memory of the nameless than that of the renowned. … Historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless.’

There is another intriguing history of memorialisation in Port Bou, occulded by this grander, European gesture. In 1979 a little plaque in Catalan was set in the cemetery wall. It reads ‘A Walter Benjamin – ’Filòsof alemany – Berlin 1892 Portbou 1940’, and in the context of post-Franco Spain appears to hint at the possibility and necessary recovery of a non-Fascist German tradition. Inside the cemetery too is another memorial stone, this time from 1990. It bears a very famous line from Benjamin: ‘Es ist niemals ein Dokument der Kultur, ohne zugleich ein solches der Barbarei zu sein’, then in Catalan: ‘No hi ha cap document de la cultura que non ho sigui també de la barbàrie’. In English this line from ‘On The Concept of History’ reads, according to the Selected Writings, ‘There is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’. Monuments to civilisation and culture are frequently also monuments to barbarism. Benjamin is clear, taking his line from Marx, that the oppressed are constantly robbed of their history and their memory is always ‘in danger’ of eradication, undermined, ‘in favour of the grand and official narratives of power, the ‘triumphal procession in which today’s rulers tread over those who are sprawled underfoot’, whereby historical memory is ‘handed over as the tool of the ruling classes’. In the preparatory note for ‘On the Concept of History’, he criticizes historical recounting that depends on recounting the antics of glorious heroes of history in monumental and epic form, and is in no position to say anything about the ‘nameless’, those who are the toilers in history, as much as those who suffer the effects of historical agency. His own mode of ‘historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless.’ It is able to remember the repressed of history who were its victims and its unacknowledged makers.

Benjamin constructs a re-visioning of the past, wherein the historian bears witness to an endless brutality committed against the ‘oppressed’. This, he understands to have been Marx’s task in Das Kapital. Das Kapital is a memorial, an anti-epic memorial, pulsating in the present, insisting on redress. Marx’s sketch of the lot of labour is presented as a counter-balance to the obfuscation of genuine historical experience. Marx memorializes the labour of the nameless, whose suffering and energy produced ‘wealth’ in the vast accumulations of commodities.

What interests me here is the ways in which we might think of what could be called counter-memory or counter-memoralisation not just as the acknowledgement of an alternative mode of understanding the past, but also as an ongoing necessity, that we are constantly steered away from knowledge of our own experience. The First World War was, for Benjamin, one marker of this: in it experience tumbles in the old style, no longer matching life or language. He writes: ‘For never has experience been contradicted so thoroughly: strategic experience has been contravened by positional warfare; economic experience, by the inflation; physical experience, by hunger, moral experience, by the ruling powers.’

We of all people are aware of Lenin’s thoughts on commemoration, as evinced in his degree from 12 Apr. 1918, titled ‘On Removing Monuments Erected in Honor of Tsars and Their Servants and Developing a Project for Monuments Dedicated to the Russian Socialist Revolution (On Monuments of the Republic)’. This provided for the removal of monuments that had apparently no historical or artistic value, as well as for the creation of works of revolutionary monumental art, which took one of two forms: – (1) decorating buildings and other surfaces ‘traditionally used for banners and posters’ with revolutionary slogans and memorial relief plaques; (2) – vast erection of “temporary, plaster-cast” monuments in honour of great revolutionary leaders. These monuments were created mainly as temporary works – Lunarcharchsiki recalled Lenin stating that the monument should be not of marble, granite and gold lettering, but instead of inexpensive materials (plaster of Paris, concrete, wood). Based on the frescoes in Campanella’s City of the Sun, these were to be educational, hinges for discussion in the city, occasions for learning – each unveiling was to be the occasion for a little holiday, a lecture.

Alternatively, we could think of Debord. Debord made an extraordinary book in 1959 called Memoires with the artist Asger Jorn, famously covered in sandpaper to scar the books in its proximity on the shelf. Memoires begins with a quotation from Marx: ‘Let the dead bury the dead, and mourn them…. our fate will be to become the first living people to enter the new life.’ It is comprised of two layers, emulating the layers of memory. One layer has black ink that outlines newspaper snippets, graphics from magazines, maps of Paris and London, images of war, reproductions of old artworks, pictures of friends, hoodlum girls, people in their milieu, and the occasional thought or question from Debord. The other layer is splattered coloured inks, which lead paths from or overlap with the black inked layer. Memory is obscure, invaded, fragmented, on the cusp of disappearance. It is abrasive, cut up, destructive, involuntary – in the mode of Proust, dispersed. For the reader there is only a drift, a wandering path, with no assured meaning, a place for rag pickers rescuing the detritus of life. Countering the regimentation of time in work and the straight-ahead narrative, this book squanders time, in emulation of ruling class leisure and luxury. There are constellations, moments, evanescent points that flare up in the memoir and burn out again to be forgotten, as much as remembered.

The situationists knew that conventional forms of historical memorialization risked partaking in the society of the spectacle’s reification of everyday life. Magnificent monumentalization offered a historical survival not worth living. But they did not wish for their own erasure. They developed new strategies of memorialization, liquid ones, and as Frances Stracey puts it: ‘those commemorated were not reduced to a dead correlate of the present, frozen in perpetuity, but salvaged in a more revitalized form, ideally as a constantly shifting, eruptive force in the present and for the future.’ Our memorials should aim at being such. My paper at the conference thinks about the ways in which film, film of a cream separator, film of a twirling ceramic pig, and film of Lenin, might speak to these concerns, might speak into a world, the Soviet one, in which Lenin’s body was frozen, hardened, its dissolution counteracted in death, supposedly for ever more. It was a wrong-footed hope, but it was emblematic of the sclerosis of the state. Sometimes forgetting might be better. Sometimes remembering differently might be advised. Keeping things alive is a kind of art, if it is not to be a cult.

******************************************************************************************

AN INTERVIEW WITH PETER D. THOMAS BYGEORGE SOUVLIS

Peter D. Thomas is a lecturer in the history of political thought at Brunel University, London. He is the author of The Gramscian Moment: Philosophy, Hegemony and Marxism. He is a member of the HM editorial board and co-editor of the Historical Materialism Book Series.

The interview was conducted by George Souvlis, a PhD candidate in history at the European University Institute, Florence.

GS: Let’s begin with how the publication of the Journal of Historical Materialism began. What were the initial aspirations for it?

PT: The journal began in the late 1990s, emerging out of different seminars attended by young postgraduate students — so, largely people writing PhD dissertations — who fortuitously came together to set up the project. It was initially a rather modest project of establishing a journal where there could be debates and discussions of topics in Marxist theory, after the long seasons of “post-Marxisms.” The journal really entered into a phase of international expansion through coming into contact with people from many different countries who were studying in London or had different connections with London.

These people became involved in the broader project of Historical Materialism and gradually there emerged a development of the journal beyond the boundaries of the English-speaking world, with a very strong focus on international discussions. In other words, we attempt to rebuild some of the bridges to other left-wing and Marxist cultures in other languages which had existed previously in the 1960s and 1970s but which have been lost for generational reasons in the 1980s and early 1990s.

I can’t speak for other members of the editorial board, but in my personal view, the fundamental rationale behind the journal was a commitment to a non-sectarian approach to developing a broad forum of discussion for all of those who identified with the Marxist tradition or the Marxist traditions in many different senses. The project soon developed in the direction of an ongoing self-critique of Marxist knowledge.

The rediscovery of old debates, the initiation of new debates and the attempt to develop a type of research project for contemporary Marxist theory became our central concerns.

GS: Could you mention some continuities and discontinuities in the sixteen-year history of the journal?

PT: There have been many continuities in the journal in terms of our focus on encouraging international discussion and always reaching out to other areas of the world and comrades working in languages other than English. Another important continuity is the strong pedagogical focus of the journal; the journal is very much dedicated not simply to publishing the big stars or the established scholars but also to encouraging younger scholars and new emerging research projects.

Another element of continuity is our commitment to non-sectarian discussions and debates. We take very seriously the idea that theoretical debates in the Marxist tradition need to be conducted with the highest standards of scholarly rigor, rather than descending into slanging matches and ritualized abuse. This involves people, without negating their own political commitments, learning new ways of discussing and debating those commitments, beyond the sometimes very polemical and conflictual environments of militant politics.

So, we see ourselves very much as a necessary continuation of politics, albeit at a certain enabling distance. We certainly do not promote an academisist form of Marxism, whatever that may be.

At its best, HM has functioned as a complement to existing political debates and sometimes has helped to create a type of “demilitarized” space for productive scholarly and theoretical conflicts, rather than the destructive conflicts that sometime develop under the pressures of the conjuncture and the urgency of certain forms of militant politics.

The discontinuities are also noticeable. There have been different generations or phases of involvement on the editorial board. Some people for different reasons decided to become engaged in other projects or found their interests moving in other directions. We are thus always looking for the involvement of new members of the editorial board, seeking to connect with younger generations and thus developing an ongoing transmission of the political culture we have tried to develop.

GS: What do you think is the position of the journal in relation to other Anglophone left-wing journals/magazines like New Left Review, Socialist Register, Red Pepper, or Jacobin?

PT: All of these journals are committed to broad discussions on the Left in different ways, and I think they should all be seen as complimentary elements of the broader contemporary left-wing and Marxist culture. In my personal view, I would suggest that one of the distinctive features of Historical Materialism is that we aim very seriously not at being an academic journal in a narrow professional sense, but at being a serious scholarly research journal.

Thus, the majority of the articles we publish are serious research papers that have emerged from long-term research projects; engagement with immediate political disputes or with contemporary political issues may very well figure in such articles, but that is not usually the primary focus. There is a certain “time” of theory, or temporality of theoretical practice, as Louis Althusser would have said, and we have tried to respect that temporal dimension, to enable the space for reflection and theoretical elaboration.

In terms of our relations with other Marxist journals in English, which I think also includes many other journals in addition to those you mention, such as Rethinking Marxism andScience and Society in United States,Thesis Eleven in Australia,Capital and Class in the UK, and so on, I think members of the editorial board ofHM regard those journals as our comrades and collaborators in building a new left-wing theoretical culture of discussion and debate.

The focus of Historical Materialism, however, is in my view unapologetically theoretical, in a scholarly rather than academic sense, rather than directly interventionist (other members of the editorial board have different perspectives on this question — my comments should not be taken as an “official” position of the editorial board, which does not exist). I think that theoretical work, serious scholarly historical work, serious philosophical work, can make a very important contribution to the broader culture of the Left and to political activity as well.

I don’t think that it is useful or productive for people working in Marxist theory today to feel intimidated by some of the older divisions between an academic and an activist Marxism that emerged from the impasses encountered by the New Left. Theory also is a very important component of political practice, and theoretical practice has an important contribution to make to the broader culture of the Left, as one of our many “resources of hope.”

The Left needs places such as Historical Materialism and other journals to develop the theoretical tools which can then be taken up by all of us in different practices and political struggles.

GS: Another significant aspect of the Historical Materialism initiative is the conferences that it organizes which have a global character, considering that they are now held annually in four continents (India, Europe, Australia, USA/Canada). Would you like to comment on the origins of this and its transformation through time?

PT: The Historical Materialism Conferences started in 2004. We held the first conference here, at Birkbeck College in London. It was quite a small gathering, sixty or seventy people, and it involved the collaboration from the beginning with Socialist Register and the Deutscher Prize Committee. It was an attempt to draw together and to connect with some of the older traditions of Marxist theoretical publishing and a new generation.

We really moved decisively the next year, in 2005, to expand our international focus, particularly in Europe at that stage, and in increasing years we have been working hard to be in contact with comrades in Latin America, in South Asia, in South-East Asia, in North America and in many other parts of the world including Africa and the Arabic speaking countries. We have had success in building bridges with some cultures more than others, but we continue to try to reach new discussion partners.

It has been an intense process of expansion: the conference grows each year, there are more and more proposals for panels and for papers. This year we received well over two thousand proposals for papers, though we only had room to accommodate a very small number of these — around 300. International interest has been expanding for a number of years now, with conferences in other parts of the world, such as Toronto, New York, Sydney and Delhi. We are presently engaged in ongoing discussions about organizing conferences in Berlin, in Vienna, in Moscow, in Rome, in Athens and in Brazil.

I think that we can explain this international interest in terms of comrades working in other countries identifying the type of conferences we organize as Historical Materialism as a distinctive model of discussion and debate on the Left. We offer space for theoretical reflection and serious theoretical debate, we do not tolerate sectarian polemics, and we insist that comradely and civil standards of debate are respected, even when people have strong and passionate disagreements.

We are also keen to create a space of discussion in which theory and politics can organically grow together; but as the young Marx teaches us, that means not only that theory should go towards politics, but also that politics should come towards theory.

I would thus suggest that in some sense the Historical Materialism conferences represent a space for a political form of “theoretical practice,” to use an Althusserian phrase (and again, this characterization is one with which many of my fellow editorial board members, non- or anti-Althusserians, certainly will not agree!). I think that our attempt to build the Historical Materialism conferences as a distinctive space of theoretical reflection on the Left has been successful if we judge by the number of people who come to the conferences regularly year after year and have identified these conferences as important spaces for the development of their own work.

It has also been successful judging by the wide international interest in holding events similar to the Historical Materialism conference in many other countries, either in direct collaboration in the journal or as independent initiatives (the recent conference held in Paris, Penser l’émancipation, could be taken as an example of the latter model, inspired in some ways by Historical Materialism).

I think the combination of these elements indicates that Historical Materialism has played a small modest role of leadership in promoting new models of discussion and debate on the Left; but it also indicates that there was a readiness amongst the left and amongst Marxists around the world to work together towards finding these new forms of debate and discussion.

I think that one of the reasons for such an interest has also been the fact that the upturn in social struggles over the last decade has been accompanied by a renewed need for theoretical clarification and preparation for future struggles. The conjuncture has thus given rise to a sort of ‘fortuitous encounter’ between theory and practice.

GS: The conferences have succeeded at creating a new solid radical milieu around them. What else has HM accomplished?

PT: I think we have helped to create a space where there are ongoing discussions from one year to the next, which has led to the emergence of new and collective research projects out of Historical Materialism conferences. That has occurred not only in the sense of publications being produced, journal articles, edited collected volumes, and so forth, but also in terms of other conferences emerging from those workshops and seminars.

For a long period, in the 1980s and 1990s, the bridges of the international left collapsed and there was very little regular exchange between different national-theoretical cultures, with some important exceptions. We have attempted to create a space where there is more regular and ongoing contact between different cultures. The success of these efforts up to now is obviously only partially due to the efforts of the Historical Materialism editorial board; equally if not more important has been the enthusiasm with which people have responded to our initiatives, which is what has made them such a success.

Another distinctive feature of the conference of Historical Materialism this year in London was the fact that a lot of panels focused on discussions regarding the current feminist trends.

I think this is a fundamental and decisive development, and one towards which we have been working for very many years. We have been trying for over a decade to reinitiate the Marxist-feminist discussions which, for many difficult reasons, in some countries and some cultures on the Left internationally, had fallen apart after the upsurge of very interesting work in the 1960s and 1970s.

In some cultures, such as Germany, there was a continuing Marxist-feminist dialogue that was very productive, and continues today to produce important new work. In English-speaking world, for different reasons, there was a collapse of the important and integral contacts between important sections and Marxist and feminist theory.

Today, though, we are witnessing a new generation of young women — but also of queer theorists and people from other traditions — engaging with these questions and making an essential contribution to the new theoretical debates.

In my personal opinion, any future vibrant Marxist theory will necessary simultaneously be a socialist feminist-Marxist theory. We cannot develop Marxist theory without this central component, without theorizing one of the core areas of capitalist exploitation and oppression.

We are continuing to promote these discussions and debates and make them not simply one part or one disciplinary area of Marxist discussions, but absolutely fundamental to debates in all areas of Marxist theory. The response that we have received over the last years to these initiatives indicates that there is a lot of energy, particularly amongst younger socialist feminist theorists, to expand this project.

___________________________________________________________________________________

HM 2017 Conference (see here for more details)

Organised in collaboration with the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Committee and Socialist Register.

Plenary sessions

– Andreas Malm’s Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Lecture ‘In Wildness Is The Liberation Of The World: On Maroon Ecology And Partisan Nature’ on Friday evening

– Panel on ‘Value and Value Theory’ with David Harvey, Michael Henrich and Moshe Postone on Saturday evening

– Closing plenary on ‘Race, Migration and the Left’ on Sunday evening

Streams

– The Great War, the Russian Revolution and Mass Rebellions 1916-1923

– Marxism, Sexuality and Political Economy: Looking Forwards, Looking Backwards

– Green Revolutions?

– Marxist-Feminist Stream

– Race and Capital

One hundred years ago, hailing the Russian Revolution, Antonio Gramsci characterised the Bolsheviks’ success as a “revolution against Capital.” As against the interpretations of mechanical “Marxism,” the Russian Revolution was the “crucial proof” that revolution need not be postponed until the “proper” historical developments had occurred.

2017 will witness both the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Marx’s Capital. Fittingly, the journal Historical Materialism will celebrate its own twentieth anniversary.

In his time, Gramsci qualified his title by arguing that his criticism was directed at those who use “the Master’s works to draw up a superficial interpretation, dictatorial statements which cannot be disputed,” by contrast, he argues, the Bolsheviks “live out Marxist thought.” From its inception, Historical Materialism has been committed to a project of collective research in critical Marxist theory which actively counters any mechanical application of Marxism qua doctrine. How the Russian Revolution was eventually lived out — with all of its aftershocks, reversals, counter-revolutions, and ultimate defeat — also calls not just for a work of memory but for one of theorisation.

We might view the alignment of these anniversaries, then, as disclosing the changing fates of the Marxist tradition and its continued attempt to analyse and transform the world. Especially once it is read against the grain of the mechanical and determinist image affixed to it by many of the official Marxisms of the 20th Century, and animated by the liberation movements that followed in its wake, the work-in-progress that was Capital seems vitally relevant to an understanding of the forces at work in our crisis-ridden present. The Russian Revolution, on the contrary, risks appearing as a museum-piece or lifeless talisman. By retrieving Gramsci’s provocation, we wish to unsettle the facile gesture that would praise Marxian theory all the better to bury Marxist politics.

Gramsci also remarks that Marx “predicted the predictable” but could not predict the particular leaps and bounds human society would take. Surveying today’s political landscape that seems especially true. Since 2008, we have witnessed a continuing crisis of capitalism, contradictory revolutionary upsurges — and brutal counterrevolutions — across the Middle East and North Africa and a resurgent ‘populist’ right represented by Trump, the right-wing elements of the Brexit campaign, the authoritarian turn in central Europe and populist right wing politics in France; the power of Putin’s Russia and authoritarian state power in Turkey, Israel, Egypt and India. Even the “pink tide” of Latin America appears to be turning. Disturbingly, we seem to face a wave of reaction, and in some domains a recrudescence of fascism, much greater in scope and intensity than the revolutionary impetus that preceded and sometimes occasioned it. There is a new virulence to the politics of revanchist nationalism, ethno-racial supremacy, and aggressive patriarchy, but its articulation to the imperatives of capital accumulation or the politics of class remains a matter of much (necessary) debate.

This year’s Historical Materialism Conference seeks to use the “three anniversaries” as an opportunity to reflect on the history of the Marxist tradition and its continued relevance to our historical moment. We welcome papers which unpack the complex and under-appreciated legacies of Marx’s Capital and the Russian Revolution, exploring their global scope, their impact on the racial and gendered histories of capitalism and anti-capitalism, investigating their limits and sounding out their yet-untapped potentialities. We also wish to apply the lessons of these anniversaries to our current perilous state affairs: dissecting its political and economic dynamics and tracing its possible revolutionary potentials.

*****************************************

The HM conference is not a conventional academic conference but rather a space for discussion, debate and the launching of collective projects. We therefore discourage “cameo appearances” and encourage speakers to participate in the whole of the conference. We also strongly urge all speakers to take out personal subscriptions to the journal.